Hello, I’m Shelley Tremain and I’d like to welcome you to the fifty-first installment of Dialogues on Disability, the series of interviews that I’m conducting with disabled philosophers and post to BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY on the third Wednesday of each month. The series is designed to provide a public venue for discussion with disabled philosophers about a range of topics, including their philosophical work on disability; the place of philosophy of disability vis-à-vis the discipline and profession; their experiences of institutional discrimination and personal prejudice in philosophy, in particular, and in academia, more generally; resistance to ableism, racism, sexism, and other apparatuses of power; accessibility; and anti-oppressive pedagogy.

I acknowledge that the land on which I sit to conduct these interviews is the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and Anishnaabeg, covered by the Upper Canada Treaties and directly adjacent to Haldiman Treaty territory. I offer these interviews with respect and in the spirit of reconciliation.

My guest today is Tommy J. Curry. Tommy is Professor of Philosophy at University of Edinburgh where he holds a Chair in Africana Philosophy and Black Male Studies. His research is primarily concentrated in Critical Race Theory, Africana Philosophy, and Black Male Studies, focusing on the historical development of disciplinary ideas, as well as why current categories such as gender, feminism, integration, and the human provide limited explanations of the horrors of anti-Black violence. He is the author of The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood (2017), which won the 2018 American Book Award, and Another White Man’s Burden: Josiah Royce’s Quest for a Philosophy of white Racial Empire (2018). Curry loves playing tennis, stringing racquets, chess, and Xbox.

Welcome back to Dialogues on Disability, Tommy! You did an interview with Dialogues on Disability in June 2015 and joined Audrey Yap, Jesse Prinz, and me for the second anniversary installment of the series in April 2017. A lot has happened in your life since June 2015, including some very frightening events and some very hopeful ones. I invited you back to Dialogues on Disability so that, among other things, you would have another opportunity to describe these situations and events in your own terms. Let’s begin with your decision to leave Texas A & M and the events that motivated it.

Yes, I would say a lot has occurred since my initial interview four years ago. Given the headlines surrounding the alt-right attack and the reputation of Texas A & M University as a historically conservative and racist institution, it should come as no surprise that I experienced outright racial hostility there. The Department of Philosophy at Texas A & M had never promoted a Black person to the rank of full professor nor has there been more than one Black philosopher on faculty at any given time between 1968 to 2016-17. During my time there, I recruited the first Black student into the graduate program and, since then, have seen three Black men, one Latino, three Latinas, and two white students successfully through their graduate education. Some would say that is success for only nine years, but it was always an uphill battle. Critical Race Theory, Africana philosophy, and Black Male Studies simply were not afforded the same kind of importance as other research.

I think this disregard became very clear when I was attacked by Rod Dreher on The American Conservative. Debates concerning the use of revolutionary violence or the ethics of Black self-defense are common areas of discussion and research in Critical Race Theory and Black Studies. Violence against Black people, Indigenous nations, and immigrant populations has, for centuries, enforced white supremacy and habituated white citizens into accepting anti-Blackness throughout the Western states. To imply that a Black full professor’s research is subject to dismissal by a white blogger is professionally insulting, suggesting that the intellectual productions and research by Black professors do not require specialized knowledge and are merely opinions that can be evaluated and discounted by your everyday white person.

As in every philosophy department, some of the philosophers in the department at Texas A & M teach horribly racist texts. Some of them teach the Nazi philosopher Heidegger; some teach feminists like Susan Brownmiller who argued, based on Menachem Amir’s sub-culture of violence theories, that Black men are more prone to rape than whites; some of them teach about revolutionary class struggle through Marx; but these ideas are not regarded as threatening. What is threatening is when a Black male philosopher teaches about Huey P. Newton who attained a Ph. D in Philosophy in 1980 from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Newton wrote about armed self-defense because he was influenced by Robert F. Williams, a veteran and lawyer, who started the Black armed guard. These conversations concerning the justifications of violence against white America are so threatening that white supremacists and a blogger (Dreher) inspired the President of Texas A & M, Michael Young, who in order to save face with his conservative base, issued a statement that condemned my research.

After the alt-right attack, I realized, I guess, that Black scholars should not settle for merely surviving in these racist environments; that we should seek out a world where we can thrive. For a while, I wanted to stay at Texas A & M because it is so close to the city that I’m from in Louisiana. But the threats and marginalization of Black, Brown, and Asian scholars throughout the institution motivated me to look elsewhere. Non-white philosophers and scholars deserve both to have their work respected and to be judged on their merit. It is wrong for Black philosophers to limit the expression of their ideas and arguments because they fear white backlash, racial violence, or ostracism by the profession. Black men, especially, fear that they won’t be hired if they appear too radical and don’t fall in line with white liberal thinking. After the attacks, I had to be honest: a Black man writing about radical Black philosophy, armed self-defense, and white feminism’s participation in the murderous project of imperialism was more offensive to white America and many universities than teaching the philosophy of Nazis, imperialists, and alt-right racists in many departments throughout the United States.

And I want to be clear here. There were several philosophers and philosophy departments, as well as other scholars and institutions that interviewed me for jobs in the United States, who understood the value of both my work and voice in this crucial moment in America. An amazing group of scholars at Texas A & M University supported me and my work throughout my career there and took on the administration without hesitation. But in the end, I grew tired of the “place” that had been created for non-white scholars at that institution. I was born at the end of segregation in Louisiana and know what Jim Crow feels like. So, I looked at positions internationally, beyond the chaos of American race conflicts, and came across the University of Edinburgh.

What are your goals for your work at University of Edinburgh? How do you hope to use the Chair in Africana Philosophy and Black Male Studies that has been created for you? And what impact do you think the Chair will have on the underrepresentation of Black philosophers in the U.K.?

I think my primary goal is to expand our understanding of the relationship between racism, dehumanization, and sexual (phallicistic) violence. I see so much suffering in the world that only appears on philosophy’s radar if it supports some narrow theory of identity. We pay attention to violence against nondisabled women because feminism tells us to do so, but the abuse, forced labour, sexual assault, and murder of children is not discussed. The rape of subordinate men and boys is not discussed. Under our current disciplinary practices, our current categories determine what we see; we need to see more, consider more, and study more.

I hope to use my position as Chair of Africana Philosophy and Black Male Studies to bring attention to the geopolitical conditions and dehumanizing logics that legitimize lethal violence and cultivate racial violence so that we can see all the violence and suffering endured by humanity without morally permitting violence against the groups that we deem less worthy of attention. Africana philosophy and critical race theory expand our considerations because they allow us to see the structures and machinations that breed and cultivate violence, despite what our ideological norms compel us to believe. Nevertheless, racism of America has restricted how we have come to think about our projects and limited much of our scholarship primarily to the United States and the Caribbean.

My hope is that the kind of research that I do will attract scholars from across the world. The U.K. university is sorely in need of racial diversity. The 2018 Equality in Higher Education Report indicates that there are only about 3400 Black professors in the U.K. In other words, they comprise roughly 2% of the academy in the U.K. Only 120 of them are full professors; and only 6 of them are philosophers. So, in many ways the underrepresentation of Black scholars and philosophers in the U.K. is worse than it is in the U.S. I can only hope that my position will aid and complement the work to diversify faculty and students throughout the country.

I perceive a different attitude towards Africana philosophy at Edinburgh. The chair of the department, Nick Treanor, has demonstrated a real desire to change how philosophy is constituted on both sides of the Atlantic. Quick to nickname me Hume Jr., Nick understood the significance of a Chair in Africana Philosophy and the first hire of a Black philosopher since the University’s founding in 1582. One of the opportunities that I’m most excited about is starting a Centre for the Study of Racism, Dehumanization, and Violence at Edinburgh. This Centre will, of course, take up central questions around anti-Blackness and white supremacy; but, I am also very invested in developing new paradigms by and through which to understand sexual violence and the marginalization of racialized males. My hope is that once the Centre is up and running, the University of Edinburgh will be a hub for coordinating Black scholars, throughout the world, who are interested in Africana philosophy, the Black radical tradition, and Black Male Studies. Will this result in hires in other U.K. institutions? I don’t know; but it is an effort to create something that has never been created before.

Since our interview in June 2015, you seem to have increased the amount of research that you do on disabled black men, as well as the scope of this research. How has your work on disabled black men developed in the past four years? And will this research continue in these directions at Edinburgh?

As you know, my research has focused on the multiple vulnerabilities that Black men and other racialized/subordinate males in the U.S. suffer. I am very concerned about how disability and pain management for Black males are theorized and treated in the U.S. Our current formulations of race and racism lead us to think of disability as an added social stigma, a dilemma of the person rather than the experience of the person themselves. This is especially important regarding Black males because the construction of Black men and boys as sexual predators and social deviants makes the consideration of Black males as vulnerable to violence or scapegoating almost impossible. In particular, I am interested in the sexual vulnerability of Black males to sexual assault and how we can better understand the disability that many Black males undergo when injured from societal violence.

I am greatly troubled by the silence of philosophers about the rape of a disabled Black man by Anna Stubblefield. A white woman raped a vulnerable Black male; yet, not a single conference session by Black philosophers or feminists has addressed the suffering of D.J. So, for all the discussions and activism around gender and sexual violence, D.J was denied vulnerability as a Black-man and as a disabled body. This is an egregious offense, tolerated only because he is a body thought to have no humanity or conscience worthy of recognition.

Since so little has been written about disability and Black men and boys, I hope to develop a substantial literature that investigates the social positionality and institutional discrimination against disabled Black males. As I have said many times, we must aim to study all racialized males and their experiences within a Black Male Studies paradigm. It is no longer adequate to assume able-bodied-ness or the absence of pain or suffering in our theorizations about the world. These considerations must be married to the constitution of the subject position. Academics should not attribute disadvantage based only on our biased observations and distanced interests.

Tommy, since we did the interview in June 2015, you and your work have received considerable attention. In addition to the new chair at Edinburgh, you have won numerous awards and accolades. How has this increased public recognition of your research affected your academic and personal life? Has this increased public recognition played a role in your decision to devote more of your research to disabled black men and violence?

Yes, since our previous interview, The Man-Not (2017) won the American Book Award, Diverse Magazine named me one of the leading emerging scholars in the U.S., and I received the Alain Locke Award in Public Philosophy from the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy.

The Man-Not has sold several thousands of copies since its release. I think it is cool and humbling to have people know your work and quote your book in various articles and publications. But mostly, I think that the awards have really legitimized Black Male Studies as a legitimate field and area of research. I never was into the academic celebrity model of scholarship. My dream has been to direct an institute that addresses much of the violence and trauma that we identify in research, influencing policy makers and opinion makers. I want to decrease violence and suffering in the lives of oppressed people; so, the increased public recognition has allowed me a larger platform and voice from which to advocate for racialized males.

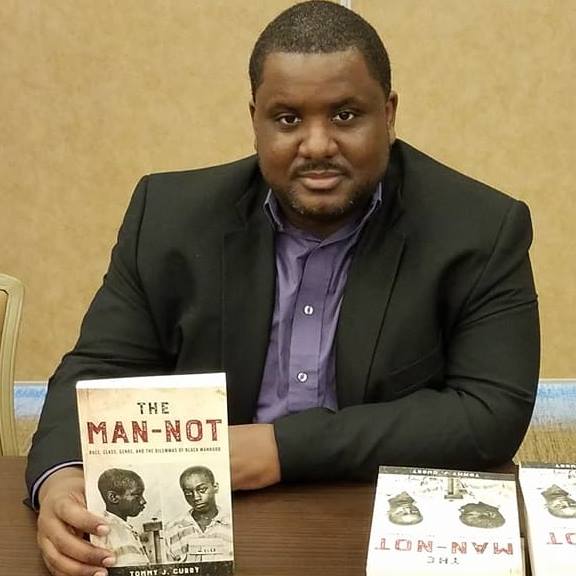

[Description of photo below: Tommy, who is wearing a suit jacket and button-down shirt, sits behind a table at a book launch for The Man-Not. He is looking directly at us. With his right hand, Tommy is holding a copy of the book upright in order to display its cover. The cover of the book comprises two police mugshots of George Stinney Jr., the title and subtitle of the book, and Curry’s name. Additional copies of the book are stacked on the table.]

The recognition has not really played a role in my decision to devote more research to disabled Black men. I have begun to write more about disabled Black men because of my personal experiences. For most of my life, I was affected by extreme pain and have experienced racism and discrimination. I don’t see anyone outraged by the suffering and experience of disabled Black people. I don’t see this conversation in Africana philosophy or the philosophy of race. I cannot think of any good reason why it is not front and centre in discussions about how we think of Blackness or the history of racism. Disability-pathology-deformity have a long history in racist accounts of various human beings. To ignore that we are dealing with white supremacist idealizations of the perfect human form in our discussions about racism, seems dishonest given the archive.

I do my work as a Black philosopher from a deeply held belief that Black scholars have a responsibility to share our research and convey the most accurate and empirically situated research about the Black experience available. While the awards and the public recognition that the research has brought have certainly been welcomed, I really take pride in knowing that I received them because I have dedicated my life and work to the personhood and humanity of Black people in the United States.

On social media, you repeatedly draw attention to issues surrounding violence, especially intimate partner violence, in marginalized communities. In your view, what philosophical research needs to be done in this area?

We need so much more work and sophistication in how we understand intimate partner violence (IPV), child abuse, and sexual violence in our communities. I often share Facebook posts about cases of female-to-male violence, as well as various stories documenting the kinds of abuse, be it child abuse or spousal abuse, that come to my attention. Philosophy tends to prefer outdated and ideological accounts of IPV that stem from the Duluth model. This model has its origins in second-wave feminist thinkers and was developed by Ellen Pence and Michael Paymar. One of the central assumptions of this model is that men are socialized to abuse women and children for power. Towards the end of her life, Pence wrote an article saying that much of the Duluth model had been merely asserted from jingles and the ideological biases of the workers interpreting the stories. CDC data and various studies have shown that incidents of IPV vary based on class status, racial/ethnic group membership, neighborhood, and alcohol/drug consumption.

Despite the overwhelming empirical evidence surrounding IPV, many philosophers ignore the science for ideology. This is especially egregious when studying Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities. Because white scholars have money to conduct in-depth research about intra-racial violence, there is a seemingly endless amount of scholarship on the link between adult perpetration of IPV and previously experienced childhood trauma, sexual assault and abuse, or depression. Many white scholars have rigorously tested Duluth and developed ecological models that show how environmental conditions (such as poverty, previous violence, and mental illness) are responsible for IPV, rape, and various kinds of interpersonal conflicts.

Ecological paradigms mean that violence between whites is situational and a public health issue that can be solved with more economic resources, healthcare access, and compassion. As such, we study white intra-racial violence as solvable, whereas poor Black, Brown, and Indigenous populations are thought to be naturally violent. Black scholars overwhelmingly endorse the Duluth model within various feminist and intersectional analyses, suggesting that masculinity builds legitimacy through violence. Like Brownmiller’s use of Wolfgang and Feracutti’s subculture of violence thesis to explain the connection between masculinity and rape, Duluth asserts that masculinity is a primary cause for the violence that women and children suffer.

Philosophy as a discipline has a real problem with respect to how it frames violence. Currently, the mainstream conversations around violence are dictated by asserting that “x group has power over y group, so x group is violent towards y group.” The formulation has become the mantra of many papers and presentations across the discipline and is largely unquestioned and accepted by philosophers. If you want to say whites are violent towards Blacks, men are violent towards women, heterosexuals are violent towards homosexuals, then you can, for the most part, simply state these large historical trends with little to no evidence and without data to support these assertions.

But what if you want to study intra-group violence or how oppression produces violence within certain groups? What rubric or theories do we have that can account for these violent dynamics? In the case of racialized men, the mainstream view allows these groups to be scapegoated as disproportionately perpetrators of IPV, sexual predation, and child abuse, with little to no recognition of their victimization by these very same kinds of violence, without any kind of evidence that they are most of the perpetrators in any given case.

Intra-racial violence tends to accumulate around poverty, societal marginalization and discrimination and oppression. While it is commonplace to simply assert that racialized men abuse and kill women and children at higher rates because they are patriarchal or hyper-masculine, the data simply does not support these assertions. For example, across the world, women are overwhelming the primary abusers of children. If we took this at face value, one could assert that women are violent towards children because children are weaker, and women aim to patriarchally dominate them; or, at least, that is what bell hooks says in The Will to Change.

When we look at social science literatures and data, however, we find that previous abuse and trauma, poverty, and stress tend to be associated with female violence against children. So poor women, Black women, the female caretakers in other racial groups are not more violent; they are more marginalized. And racialized men are not innately violent towards children either, because we also find that when the biological father of the children is in the home, he decreases the risk of abuse to the children overall. Why? In any given oppressed group, one of the effects of oppression is the internalization of the group’s vulnerability and disposability created by the group’s ostracism. This does not mean that the oppressed group simply assimilates the ideas of the dominant society at a psychoanalytic level, but rather that the social conditions and psychological violence experienced over time have some effect on behaviours, rationalizations, and the mediation of personal relationships. We know that with Black-Americans, for instance, most IPV occurs in lower socio-economic classes, that Black men and women have similar rates of as victims and perpetrators of IPV, and that violence emerges in various personal and intimate relationships.

Philosophy does not currently offer any thinking or theory as to why these marginalized groups disproportionately endure intra-group conflict. Usually, assertions that oppressed groups suffer from intra-group violence are considered heresy. The assumptions that philosophers hold about IPV and child physical and sexual abuse are really universalized descriptions derived from what social scientists and feminists asserted as causal amongst white families and in white communities. When we look at racial groups, IPV victimization rates between Black, Latino, and Indigenous men and women in the U.S. are roughly equal and have a much different etiology than IPV victimization between whites. Much of the intimate partner violence in racial groups is bidirectional, not unidirectional, as Duluth assumes, meaning that both partners are abusers and victims.

We see the same thing with child sexual abuse. Black males have the earliest sexual debut, often before their fifteenth birthday; but many of them do not see themselves as susceptible to rape, even though in most states fourteen is well below the age of consent. Many of these early sexual encounters are in fact statutory rape. The world is far more complicated than our current theories and intuitions assert. Philosophers, because they are scholars, have a responsibility to get these arguments and theories right. It is not enough to strongly believe an argument. We must get around to demonstrating that our claims are factual and encourage, rather than condemn, philosophers willing to look at various aspects of violence and vulnerability beyond established identity politics.

That said, I do believe that philosophy could significantly contribute to how we construct and deploy assumptions about causality and the normative subject in our analyses of violence, adding a great deal to how we think about internalized oppression and societal violence more generally. Unfortunately, our field is more interested in protecting certain ideas from falsification than theorizing from empirical evidence to generalizable theories about the violence in disadvantaged populations and marginalized communities.

Your work has become widely acknowledged and recognized outside of philosophy. Some academics, who are not philosophers, refer to you as “the People’s Scholar.” What do you take this title to mean? How does it reflect your critique of disciplinarity? And lastly, do you want to recommend books or articles on any of these subjects or some other topic?

Yes, I am tremendously humbled by the reach of my research outside the academy. When I finished my Ph.D. in 2009, lots of scholars discouraged me from speaking primarily to Black and Brown folks. They did not believe that a philosopher could gain national prominence with a research agenda dedicated strictly to problems of race and racism, especially if said scholar did not direct such research at a liberal white academic audience. I did not try to get on mainstream liberal networks or become a celebrity intellectual in that way. My primary focus was to educate our communities about the causes and complexities of racism and violence in the United States.

To be called “the People’s Scholar” is truly an honour. It means that my research resonates with oppressed and marginalized communities and groups, that they can see their concerns and experiences in my words. I may not have all the answers yet, as I am still fairly early in my career, but to be called the People’s Scholar lets me know that I am asking the right set of questions and that an audience is listening. I care deeply about the violence in poor Black communities. Because I grew up in a poor Southern town, I saw various forms of conflict and abuse. These events affected me, and my connection to real people and, most importantly, given my research on Black male sexual victimization, to real victims, is central to how I think about my writings and public talks.

When I first started hearing and studying this violence it shook me to my core. Sometimes during my talks, I need to hold back tears because I think about the voices and pain that many of these Black men have shared with me. But that burden is far less than the lives lost from racist violence and the de facto segregation that still exists in this country.

I suppose that this emotional weight is what drives my concern and critiques of disciplinarity. Disciplines enable far too much idle thinking to truly be useful for thinking about the world. They tend to deter theorists from truly thinking through complexities and conflicting evidence. Consequently, every problem has a standard answer and set of go-to sources. In my opinion, disciplinary knowledge primarily relies on tradition and professional consensus to provide legitimacy. Disciplinarity does not teach scholars how to study the world; rather, it offers researchers a way to morally condemn the evidence, the experience, and the suffering of others that would expose the limitation of, or even refute, their cherished theories.

For all the research on race and racism, how did we never run into ecological theories of domestic abuse? Why haven’t we understood or written about female-perpetrated IPV or child (sexual) abuse? How is it that all these research topics, which are taken up in many other disciplines, never crossed the mind of one philosopher of the last two or three decades? I strongly recommend that philosophers engage some texts outside of their comfort zone and standard training.

I must recommend Stacey Patton’s excellent book, Spare the Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America (Beacon Press, 2017). If you haven’t read it yet, I would highly recommend The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood (Temple University Press, 2017), and Linda G. Mills’s book, Insult to Injury: Rethinking Our Responses to Intimate Abuse (Princeton University Press, 2013).

Tommy, thank you very much for returning to Dialogues on Disability, especially given how busy you are at this time as you prepare for your move to Edinburgh. You’ve been a great supporter of the series since its inception.

Readers/listeners are invited to use the Comments section below to respond to Tommy Curry’s remarks, ask questions, and so on. Comments will be moderated. As always, although signed comments are preferred, anonymous comments may be permitted.

____________________________________

Please join me here again on Wednesday, July 17th, at 8 a.m. EST, for the fifty-second installment of the Dialogues on Disability series and, indeed, on every third Wednesday of the months ahead. I have a fabulous line-up of interviews planned. If you would like to nominate someone to be interviewed (self-nominations are welcomed), please feel free to write me at s.tremain@yahoo.ca. I prioritize diversity with respect to disability, class, race, gender, institutional status, nationality, culture, age, and sexuality in my selection of interviewees and my scheduling of interviews.

Follow BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY on Twitter @biopoliticalph

Note that the links to earlier interviews with Dr. Curry are dead links.

LikeLike

Caleb W, thanks very much for alerting me to this! I will correct these mix-ups!

Shelley

LikeLike

Hi again, Caleb W, I have fixed the links to the earlier interviews. Best, Shelley

LikeLike

Thanks! These are all really enlightening.

LikeLike

hi Caleb W, I’m glad you liked the interviews! Check out other interviews on the Dialogues on Disability page of BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY and all of the other great content on our blog!

Shelley

LikeLike

[…] Tommy, with Shelley Tremain. 2019. Dialogues on Disability: Shelley Tremain Interviews Tommy Curry. BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY (blog). […]

LikeLike

[…] actually think, Shelley, that Tommy Curry’s interview is extremely relevant to this issue of passing and self-protection. This passage […]

LikeLike

[…] June 2019: Dialogues on Disability: Shelley Tremain Interviews Tommy Curry […]

LikeLike