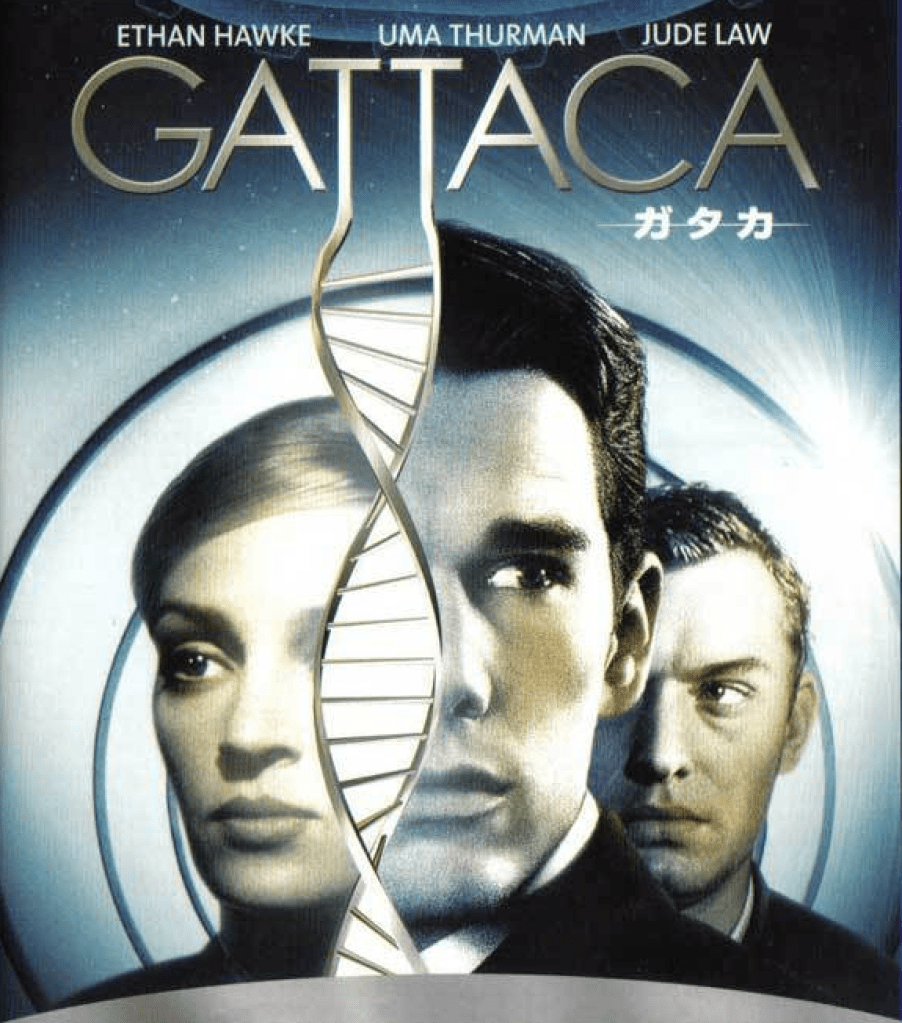

Pictured above is the Gattaca movie poster, featuring three characters in a triangular arrangement. In the foreground is Ethan Hawke (playing Vincent), a white man with short, dark brown hair. To the left is Uma Thurman (Irene), a white woman with straight blonde hair in a ponytail. To the right is Jude Law (Jerome), a white man with short, light brown hair. All characters have a serious, determined expression. A large, glowing DNA double helix stretches vertically in front of them. The colour scheme is muted, clinical shades of blue, gray, and white. The title “GATTACA” appears near the top in silver letters, connecting with the DNA helix. There are Japanese katakana characters (ガタカ) under the English title.

Gattaca

In the last week of my Ethics class at Washington University in St. Louis, I would always screen the 1997 dystopian film Gattaca, about a not-too-distant future in which parents genetically “enhance” their children to possess marketable biological traits like height, athleticism, and 20/20 vision. Pervasive genetic engineering has created an apartheid-like society in which genetically unmodified “invalids” are banned from elite schools, professions, and many common spaces. Genetic profiling is used to prevent invalids from secretly infiltrating valid-only domains.

However, an underground industry has emerged to match disabled valids with invalids who can secretly take their place in high society, for a price. One such valid is Jerome Eugene Morrow, a competitive swimmer who becomes paralyzed after being hit by a car, making him, for all intents and purposes, invalid. Jerome hires Vincent to assume his identity, and Vincent quickly secures a job as a navigator at the prestigious Gattaca Aerospace Corporation, where he had previously worked as a janitor. The hiring process consists exclusively of a genetic test, which confirms that “Jerome” has a gold-star genetic profile.

Gattaca vividly depicts what happens when a society tries to eliminate disability – and by extension, disabled people – through genetic engineering. One of its central lessons is that disability cannot be eliminated because it’s a moving target. It’s not a biological or genetic feature of individual bodies, but rather a contingent social construct. Thus, when a society tries to eliminate genetic markers of disability, it simply shifts the label of “disability” from one population onto another, creating a new disabled population that faces the same structural exclusions as the last. Ableism persists – it simply finds a new target.

This is precisely what happens in Gattaca, where people who would be considered highly able-bodied in our present society are reassigned as “invalid” in the wake of prenatal genetic engineering.

Vincent

The main example is Vincent Freeman, the protagonist. In the real world, Vincent, played by a young Ethan Hawk, would be considered highly able-bodied. He wears glasses but has no other discernible bodily “impairments.” Yet in Gattaca, he’s classified as disabled at birth because his genetic profile predicts a significant probability of heart disease, vision issues, and other medical conditions, with an estimated life expectancy of only thirty years. (Note that genetic tests are not particularly reliable, as shown in the film and confirmed by real-life science).

Regardless of his genetic “risks,” Vincent not only performs as well as valids, but consistently surpasses them at physical and cognitive feats, allowing him to quickly rise to the highest ranks of Gattaca Corporation, where he is selected for the most important mission they have ever launched. Nonetheless, he is (secretly) disabled because of his genetic profile. Gattaca thus demonstrates disability’s cultural contingency by imagining a future in which disability is tethered to genetic profile more than functionality relative to the built environment. Vincent functions exceptionally within Gattaca, yet his participation in that world is criminalized, creating the legal and institutional barriers that position him as disabled.

Irene

Irene, Vincent’s love interest, demonstrates a further dimension of the contingency, and therefore ineliminability, of disability. Within the valid caste, there are degrees of disability. Since Irene was conceived through genetic engineering, she qualifies as a valid, but she has a heart condition due the limitations of the technology. She is allowed to participate in valid-only society but is confined to its lowest echelons. She cannot be promoted beyond administrative work at Gattaca Corporation, and she is expected to date within her own (lower) genetic tier. (Inter-genetic mating, similar to inter-abled dating in our society, is stigmatized). Irene’s situation demonstrates that disability is not a zero-sum proposition: since no one’s genetic “risk” is zero, everyone is more or less disabled, and anyone’s genetic status could change as the gene-editing technologies evolve. Irene herself could be downgraded to invalid status by the next generation of “enhancements.” In this way, Gattaca shows that the quest to eliminate disability only results in its perpetual reinvention.

Anton

Vincent’s brother Anton illustrates yet another aspect of disability’s contingency. Unlike Vincent, Anton was engineered to possess an elite genetic profile, allowing him to attend valid-only schools and eventually become a police detective assigned to investigate Vincent. Yet despite Anton’s “superior” genetics, Vincent consistently outperforms him both physically and mentally. Indeed, Vincent outdoes everyone at Gattaca Corporation, because he’s the only one who works rather than coasting on genetic privilege. (The mission supervisor calls him “the best navigator they’ve ever had”). The contrast between Vincent and Anton reveals that Gattaca’s genetic crusade has not produced excellence, but instead its opposite: mediocrity. The valids are strikingly devoid of moral character, instead prioritizing physical and mental agility – qualities they also fail to cultivate beyond a superficial level. By all appearances, their most pronounced trait is obedience: they passively accept their assigned role within Gattaca’s genoic culture. This shows that able-bodiedness is not a genetic or biological marker of excellence, but rather a cultural marker of typicality or conformity. What counts as “able-bodied” shifts with the prevailing definition of “normal.”

Jerome

Jerome illuminates a further aspect of the malleability of disability. Born a valid, Jerome becomes functionally invalid after being paralyzed in a car accident. Even though Jerome possesses an elite genetic profile, his body becomes a visible marker of genetic “impairment,” making him an outcast. It’s important to note, as Elizabeth Dietz explains (2022), that prenatal genetic tests don’t simply identify genetic impairments; they create them. There is no genetic impairment simpliciter for screening technologies to detect. The causation runs the other way: first, eugenicists decide what counts as an impairment, then they create technologies to test for its genetic markers. One is not born but rather becomes disabled, so to speak. Jerome’s paralysis is not disabling per se, but it becomes a disability because Gattaca’s genetic authorities have defined it as a form of impairment, and therefore something to be excluded from society. In Gattaca, there are no ramps, curb cuts, or other accessibility features because society is designed exclusively for “normal,” interchangeable bodies.

Jerome demonstrates the malleability of disability in another way, too. He reveals to Vincent that he stepped in front of a car to end his life after coming second in a swimming competition, which is unthinkable for someone with his exemplary genetic profile. He can’t live with the knowledge that he didn’t fulfil his “genetic destiny,” chosen for him by his parents at conception. While this may seem like a trivial reason to commit suicide, in the world of Gattaca, the notion of genetic destiny is an article of religious faith. People believe in genetic predetermination with religious fervor, which is what prevents them from dating for love rather than genetic compatibility, choosing a job they enjoy instead of one for which they were genetically programmed, or believing they have any meaningful control over their lives. Everyone’s future is determined at birth, meaning that no one is free – except for the aptly named Vincent Freeman, the one character who rejects the religion of genetic determinacy and forges his own path. In Gattaca’s society of unfreedom, where genes are a currency and relationships are reduced to gene-based transactions, no one is flourishing.

This climate of general misery suggests that most if not all residents of Gattaca, regardless of social status, suffer from psychological trauma – the kind described by Franz Fanon as disabling. As a psychiatrist working in occupied Algeria, Fanon documented the psychological effects of colonialism, noting that it left indelible psychic wounds. These “reactional disorders” were not exceptional cases but the structural effects of colonialism, extending to colonizer and colonized alike. The occupying French soldiers were traumatized by the horrors they witnessed and inflicted on others, while the colonized were traumatized by the imperial violence they experienced. Although Gattaca is presented as a post-racial society, its gene-based apartheid regime appears to inflict trauma on everyone, whether valid or invalid.

Reverse Colonialism

It is worth noting that because Gattaca asks us to imagine a post-racial society in which racism has been replaced by genoism, it falls into the problematic category of “reverse colonial parable,” in which a (predominantly) white population is cast as the colonized instead of the colonizer. This genre of science fiction typically refuses to engage meaningfully with race and ignores race’s intersections with other oppressions, including ableism. In our own white supremacist society, genetic engineering would no doubt favor the selection of white “designer babies,” because whiteness is a form of cultural capital whereas racialization is defined as a form of impairment. In other words, real-world genetic engineering would lead to racial eugenics, not just ableist eugenics. The result would resemble the “post-racial” future that Nazis tried to engineer through the mass extermination of racialized populations.

I suspect that the filmmakers chose to abstract away from race to show that prenatal genetic engineering is inherently harmful – it would be harmful in even the most egalitarian society. Therefore, it should be banned everywhere, always. Imagining safeguards or utopian social conditions that would prevent abuses of prenatal genetic engineering is a form of escapism.

The Value of an Open Future

The reason I assigned Gattaca in my Ethics classes is that it demonstrates the historical and cultural contingency of disability, whose meaning shifts from one place and time to another. In Gattaca, people who would be highly able-bodied in the real world are disabled because of a theoretical probability of genetic “risk.” According to the medical model, disability is a natural property of individual bodies, an unchanging essence, consistent across time and place. Gattaca reveals this model to be not only incorrect but also harmful, insofar as it gaslights people into believing that disability could, and perhaps should, be scientifically eliminated. Attempts to eliminate disability simply reinvent it in a new guise, creating a new class of “disabled people.” Furthermore, by believing that we can eliminate disability, we grant ourselves a power that no one should have: the authority to decide who should exist.

Rosemarie Garland-Thomson writes that “one aspect of modern acculturation is to fear a future that is unpredictable and uncontrollable. The modern subject has a deep investment in a tractable future” (2012: 351). The desire for control – control over populations, genes, and the natural world – is associated with vices of hubris, egoism, and authoritarianism. Eugenicists believe they have both the right and the power to create a society in their own image – a society of “valids.” Whenever they try to construct such a society, the result is always the same: mediocrity, misery, oppression. To prevent this kind of society from being fully realized, Garland-Thomson believes we should conserve and protect disabilities, which are a “generative resource” rather than a “restrictive liability” (339). Disability provides a source of alternative ways of knowing, or “cripistemologies,” that challenge the dominant eugenic ideology. It forms the basis of rich countercultures that contest hegemonic cultural practices. And it inspires virtues of modesty, vulnerability, and care, which counteract the eugenicist’s hubristic belief in a natural genetic order that ought to be brought about. Rather than engineering disabilities out of existence, we should actively protect and preserve them.

Eliminating disability is impossible, and trying to do so only entrenches oppressive hierarchies. Yet eugenics appears to be gaining popularity, not declining. This marks a dangerous slide into fascism, a form of authoritarianism that intensifies ableist eugenics. To protect freedom, knowledge, and virtue, we must also protect and value biological diversity.