Hello, I’m Shelley Tremain and I would like to welcome you to the one hundred and fourteenth installment of Dialogues on Disability, the series of interviews that I am conducting with disabled philosophers and post to BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY on the third Wednesday of each month. The series is designed to provide a public venue for discussion with disabled philosophers about a range of topics, including their philosophical work on disability; the place of philosophy of disability vis-à-vis the discipline and profession; their experiences of institutional discrimination and exclusion, as well as personal and structural gaslighting in philosophy in particular and in academia more generally; resistance to ableism, racism, sexism, and other apparatuses of power; accessibility; and anti-oppressive pedagogy.

The land on which on which I sit to conduct these interviews is the traditional ancestral territory of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabeg nations. The territory was the subject of the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement between the Iroquois Confederacy and the Ojibwe and allied nations around the Great Lakes. As a settler, I offer these interviews with respect for and in solidarity with Indigenous peoples of so-called Canada and other settler states who, for thousands of years, have held sacred the land, water, air, and sky, as well as their inhabitants, and who, for centuries, have struggled to protect them from the ravages and degradation of colonization and expropriation.

My guest today is Sarah Gorman. Sarah has backgrounds in the history of philosophy, continental philosophy, and tech. Currently training a Large Language Model, she has most recently written on the intersection of decolonial theory, critical disability studies, and the legacy of the US secret war in Laos, as well as a piece on nursing-home abolition, which engages with the work of Marta Russell. Beyond work and philosophy, Sarah makes stuff: she paints, draws, collages, and crafts.

I want to caution readers and listeners that this interview includes discussion of domestic violence, sexual violence, and suicide.

Welcome to Dialogues on Disability, Sarah! Tell us about your personal and professional background.

Hello, dear Shelley, and dear readers. I would like to give thanks, as the Haudenosaunee do before they begin joint endeavors together.

Thank you to the people, your readers. Thanks again, Shelley, so much, for asking me to participate in this interview with you. I joked to a friend that baby Dr. Sarah with imposter syndrome would have cheered had she been called a philosopher. Now I call myself one too. I appreciate the invitation to participate in the archive of stories from disabled workers in philosophy that you have created. I am a longtime reader, even though I am no longer a worker in philosophy. (Thank goodness.)

I write from Western Massachusetts, USA, from a town inappropriately called Turners Falls. A settler massacre happened in 1676 on the banks of the river near my house. So, I join with others and call my town Great Falls, MA, because William Turner, after whom the town gets the other name, was a mass murderer. The Nipmuc and Pocumtuc are the traditional stewards of the elements here and they continue to live in, and belong within, the community.

So, I am originally from Buffalo, New York, USA. That is why I know the Haudneosaunee Thanksgiving address that I invoked earlier. I started college as a French and English major at Northeastern University in Boston and I finished as an English and philosophy major at the University of Alabama Huntsville. I am a college dropout who went back to school. I got my Ph.D. at Vanderbilt after finishing a terminal M.A. in philosophy at Miami University. So, I have lived up and down the east coast and in the mid-west. Moving to the U.S. South from Buffalo and Boston really impacted me.

I have simultaneously worked and gone to school from the time that I was twelve-years old until my second year at Miami, when I became a funded student and thus work and school became the same thing for me. I had a different relationship with work and with philosophy than many people that I know.

Coming from an elite university, Vanderbilt, I met so many wonderful people but I knew in a sense that I would not succeed in the philosophy world after being there. The faculty there is wonderful–save for the Kantians–and the other students there were so brilliant and made the experience of studying philosophy worth the tears.

The pace of life in academia was too fast for me. I knew that I could not produce at the rate that would be expected of me. I am, and forever will be, a turtle. This element of academia is criminal and I literally have no idea how you scholars live. Too fast, too furious.

[Description of image below: Photo of Sarah with her hand to her face. Her head is bent to her left and she is wearing large plastic-framed glasses.]

One thing that I think is really funny about school is how no one gets the “it takes time to learn something” thing. We can read something, but learning it, integrating that knowledge into our lives—so that it fits with our other beliefs in a kind of ecosystem way, where the knowledge becomes second nature and can be acted upon—takes time. Integration is what I call that. But you cannot predict how long that will take, or if it will happen at all. School and its current pacing completely deny this reality about learning.

You identify as a second-generation psychotic and underemployed philosopher. How do you explain these two aspects of your identity? Is there a mutually constitutive relation between them? If so, how would you characterize it?

I am a first-generation college student and a second-gen psychotic–or schizophrenic. Both my parents had schizophrenia. Well, we can talk more in-depth about my mom. She now just identifies as a survivor of violence, rather than a schizophrenic. In the 80s she was choked almost to death by an ex-lover. Her eyes bled and she had a ring around her neck that was a bruise and her tongue turned black. So, my mom is also a seraphim, and she believes herself to be one–she is truly a fucking (excuse me) angel. That’s how she identifies now. Not schizophrenic. Seraphim. Seraph? I’m an atheist, by the way.

I know that I sound like I am getting into the weeds with her story, but I think it is important to recognize that we are multiple; we are not single-bounded beings. What I am is in part what I inherited from my family. I am not even me, just me, on my own. I rely on so many others for my being.

I am eating a yogurt right now wondering how many people along its supply chain put their grit and tears into this goopy delight that nourishes me. I am puzzling over how many other hands have held its plastic tub that I will soon throw away. I silently thank the first poor bastard to let their milk clot, who was hungry enough to try it out, and discover that rancid milk is a luxurious creamy snack best accompanied with lemon curd. That person changed my life. My life is sustained, supported, and only possible because so many others came before me.

Culturally, we are super into the individual. But we are NOTHING without each other. I deny that I even AM an individual. I do not think there is a single, stable, thing called the self. In a poem called Ars Poetica?, Czeslaw Milosz writes, “The purpose of poetry is to remind us how difficult it is for us to remain just one person. For our house is open, there are no keys in the doors, and invisible guests come in and out at will.” I am a survivor of sexual violence myself. I am becoming okay with saying so in public only now, so I say this in a way that acknowledges that about me. That I am in part constituted by someone whose being I would like to totally forget and deny. We have an indelible impact on the people with whom we come into contact, and not only in “special cases” like rape or violence. There is nothing different or special about rape. Rape is violence that preys on our inherent openness to being affected by one another. I could say something in this interview that changes your life and the entire way you live. Probably won’t, but it’s possible.

The underemployed philosopher part is not so central to my identity, but I do think it is tied up nevertheless with me being a second-gen psychotic. So, I work as a tech gig worker, basically, right now. Some days there are tasks to do and some days there aren’t. I perform writing exercises that tell an AI model what constitutes a good answer versus what is not a good answer. It is fun work to do as a philosopher. It is making arguments, justifying your claims, and teaching, really. My interlocutor is just a Large Language Model now instead of a young adult.

I wish my identity as a second-gen psychotic and an underemployed philosopher were not entangled but I suspect they are. I have no qualms with telling people that I am bananas and that I have many limitations. I am and I do. I think about the U.S.’s FBI, police, and CIA entirely too much. But it is also true that the institution–that academia as a system–bears responsibility for its inhospitality to disabled bodyminds. They need to get their stigma figured out.

I realized that I was going to have a hard life (that ended early) if I tried to hack it in academia; so I immersed myself in my hobbies–art saves my life–found another way(ish) to make money, and now I do philosophy for fun. I am broke, but I like it better this way.

In principle, I only am a five (out of ten) at work. I think that I learned this about myself because I have worked in minimum wage jobs since I was super young. Maybe by saying that, I am perpetuating certain stereotypes about poor people. Ah well.

They will extract and extract and extract from you until there is no blood left to give. And, in academia, they expect you to be grateful for the privilege of it all. I do not give work my all anymore. Because it was killing me. Or rather, making me want to kill myself.

In our preparation for this interview, you told me that pathologizing yourself to obtain accommodation in the university was the worst decision you have ever made. Please explain the circumstances under which you made the decision and the consequences of making it.

First, I am going to back up a little for context and tell you some more things about me. I first learned ableism from my parents. When I was maybe eight years old, I told my parents that I had hallucinated something. Their reaction was terror: the only thing that they did was freak out because they “gave me” schizophrenia. I suppose that I both became disabled and internalized ableism that day? All I remember was that I said I was scared and then everyone else freaked out and they forgot about my concerns. I learned what to fear that day. Getting sick.

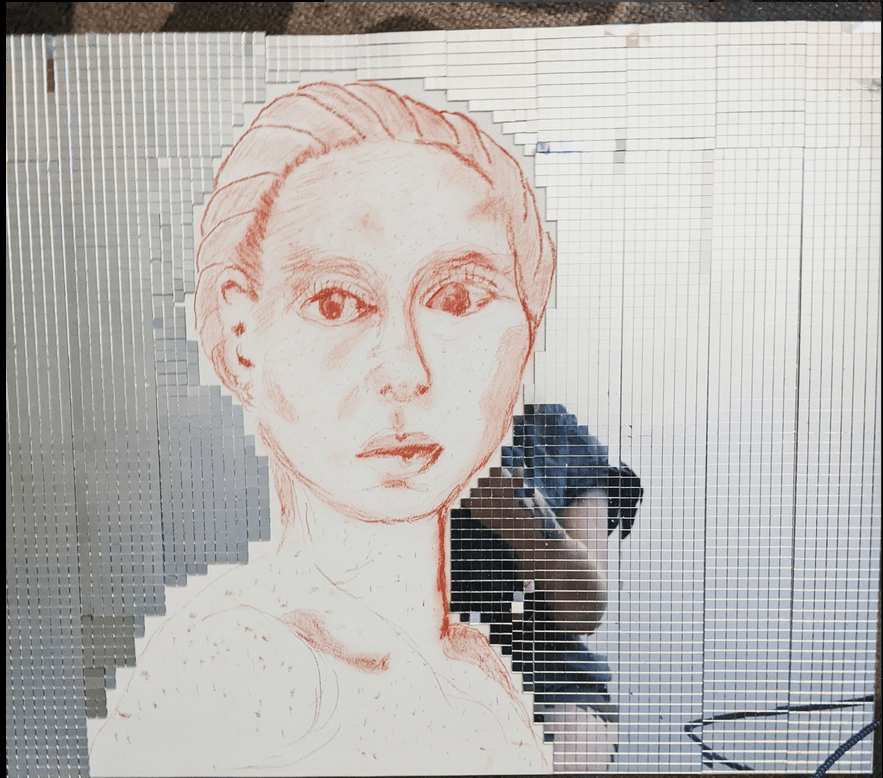

[Description of image below: A self-portrait drawing of Sarah.]

So, after that incident, I did not tell anyone when I hallucinated things. Mostly, I hallucinated before I went to sleep. But, sometimes, life got harder and my coping mechanisms went awry. Sometimes, it happened in public, worst when I was somewhere new. It happened more often the more stressed that I was. Once, I was restocking books at a bookstore that I worked at after I dropped out of Northeastern, collecting them from the basement, and a woman came downstairs and said to me “Who were you talking to?” I had not realized that I was talking out loud, and I had no idea what I was saying. Good thing that I did not have the nuclear codes.

In any case, I learned how to survive–like, really, to continue to stay alive despite inhospitality from essentially every direction–from my parents. They loved me fiercely; my mom still does. My dad is dead now; rest in peace to him. Most of their problems, it seemed to me, came not from their inability at times to square with reality; but the inability of institutions to adequately support them in their project of being parents to my brother and me.

In the United States, we do not want disabled people to have children; and the evidence that we do not is that there is a poverty line—which is about $15,000—and below that poverty line is the paycheck that we give to disabled people: about $12,000. In the United States, we give a subsistence living to disabled people (about 80% of the poverty rate) because we assume that a person will be also getting a check from their work from a short or long-term disability insurance plan and purportedly the plan from the government will not be their only income. What we do not talk about enough is people whose disability prevented them from ever having a work history at all. They are the unluckiest ones of all. They were my parents. My parents met one another outside of “the shrink’s” office, as my dad used to call his psych provider. (It’s dreamy, I know.)

So, anyway, in my childhood there was simply never enough money. When there was no money, there was no food. And when there was no food, no one could sleep and then everyone went crazy.

I have a point. I found myself in grad school having problems in school essentially for the first time in my life. My life problems were considerably smaller now that work and school were the same thing. I had always been smart enough to do well in school without trying very hard and while working at paid jobs 20-25 hours a week too. But now, in grad school I thought–I think rightly–that I was about to get kicked out because I could not complete my logic exam in the allotted amount of time for the exam. I say, I could do school before, but that was only because I dropped out of math and science and I loaded up on art, English, and French.

I went to the psych center at school because I was afraid that I was going to lose my job and my income and I did not have any kind of safety net. My parents did not even own cars, much less a house that I could easily go back to. Did I want medicine? they asked. Ugh, seeking help at the psych center, it turned out, was just the beginning of my problems.

I agreed to be medicated. That was a big mistake. I also feel like I agreed to the fact that there was fundamentally something wrong with me by agreeing to be “cured” by them; or as close as they could get to that: extraordinarily sedated.

I have been suicidal on a cyclical timer for as long as I can remember. I get by, though. I have a safety plan, a wellness council, and many loving people who help me when I realize that I have been thinking too much about which side of the bridge to jump off. I also make art which helps me not commit all the crimes against myself and others.

Having access to drugs that I could off myself with was not good. I collapsed on the ground once from too much booze and pills. Against medical advice, I also shook off the ambulance that came to help. That was the most American thing that I have ever done; that shit is expensive. THAT is why medicating me was a bad idea.

The process of applying for accommodations from the university was truly ridiculous, insulting, and was clearly meant for those students fresh from high school who knew their pediatricians’ names and could recite them from recent memory. They asked about me as a child. I took a battery of tests. Then they made me come back and take another test to prove that I was not deaf, because I failed a test where you must click when you hear a beep as there are strobing numbers on the screen chaotically switching with other numbers and patterns.

These tests were psychic torture. But science. I had to return for another test, even though I was chatting to the test administrator in between exercises–which, I presume, meant she knew that I was not deaf. I remember feeling like my eyes were going to bleed. Then, another day of testing. After the assessments, the doctor told me that “this test cannot adequately account for your intelligence.” This statement was supposed to make me feel better because they had determined that I was as slow as molasses, which I could have told them from the get-go.

“BUT, NO, YOU’RE LIKE S L O W”—as in, far, far below average speed. Very percentile low. Welp. I did not need to know the specific number. I grew up in New York State taking standardized tests for a living practically, as that is what they did to us. Slowness was why I came there. I tried to be nice.

She assured me that I was smart: “This test does not measure your capabilities adequately,” apart from the fact that I cannot multitask and I only process a fraction of the audible data that I get from my environment. She assured me that I had “above genius-level” language skills. I do not believe in genius. I just believe in white men that fancy themselves as special. I ended up getting a 98 on my logic exam when I had 7 hours to take it. I finished in 3 hours and change.

Among other publications, Sarah, you have written a chapter on child poverty and disability. Please tell us about the research that the chapter comprises.

Sure, thank you for singling out this aspect of my biography. This chapter was my first publication and I think that I tried to do too much in it. In any case, the chapter emphasizes how stigma affects individuals differently based on their intersecting identities, including race, disability, class. It discusses both the psychological and social effects of stigma. I analyze some of the work on vulnerability. I argue (aligning my work with Judith Butler’s and Jackie Leach Scully’s from an edited collection on Vulnerability) for an expanded concept of ontological vulnerability, saying that all humans are vulnerable in different ways due to our embodied nature and social interdependence. This view of vulnerability is proposed as a basis for generating political and ethical obligations.

Based on this understanding of vulnerability, I suggest an alternative political vision that: (a) recognizes and responds to different forms of vulnerability; (b) prioritizes human needs over profit; (c) transforms “non-permitted dependencies” (like health care, in the United States at least) into “permitted dependencies” (like firefighting services–services we ourselves are not responsible for providing, dependencies that are permitted); and (d) reduces stigma through representation and inclusive design. The chapter suggests several ways to combat stigma, including: (a) consulting with and involving affected individuals (including and especially children) when developing policies and research on impoverished communities; (b) sharing diverse narratives of experiences at the intersection of poverty and disability; and (c) making the built environment more inclusive.

Sarah, your dissertation, The Role of Waste in Modern Political Philosophy, drew upon psychoanalytic theory, modernity, and discard studies to critique social contract theory. Please explain discard studies for our readers and listeners and the motivation for your argument in the dissertation.

Oh goodness, my dissertation. It also tried to do too much (be a five is my mantra for a reason). I was trying to learn in my dissertation. Maybe I will be punished by someone for admitting this, but I approached my dissertation as my very own space to come to understand the ways in which contemporary forms of oppression in early U.S. political thinking are related to conceptual matters in social contract theory and other Enlightenment philosophies. My dissertation is not my first book. It was my sandbox.

I loved reading the history of philosophy, and so I wanted to do the work of reading everything that Kant ever wrote. I also think that the material world is full of traces of our philosophical ideas. To read, for example, Kant’s various essays on the concept of race, along with his work on anthropology that he taught at early and at later times in his career. To see the throughlines in his thought throughout his career and to see the way purposiveness operates as a race-anchor in his work.

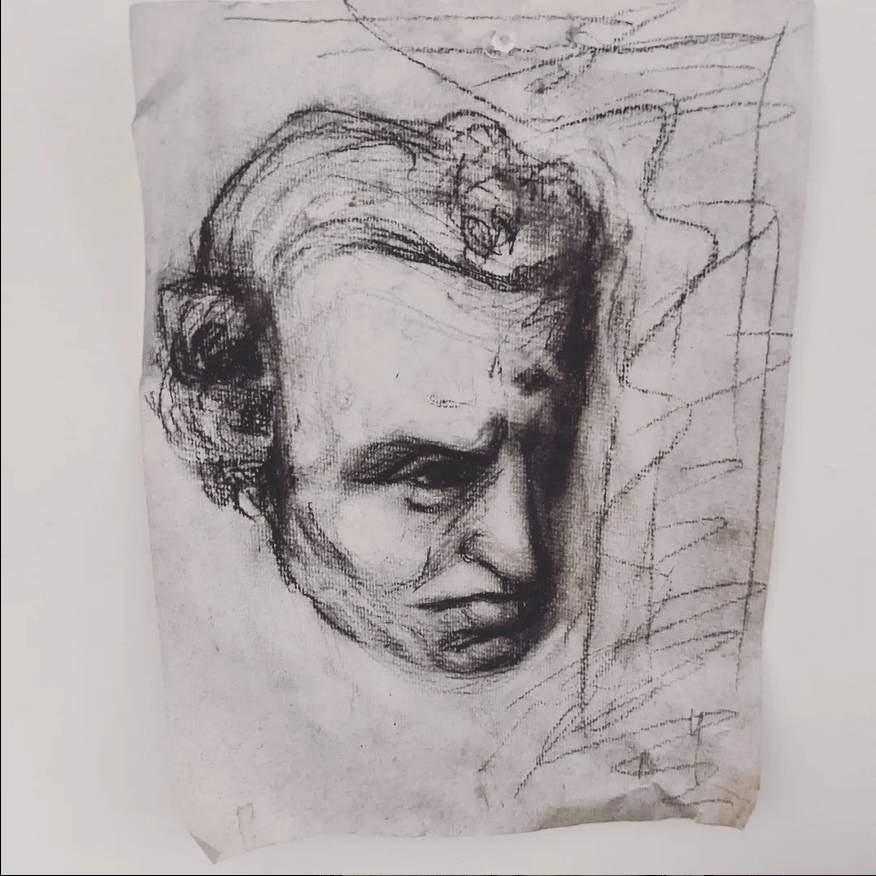

[Description of image below: Sarah’s charcoal portrait of Kant.]

Philosophers LOVE to protect Kant—even the ones that are honest about his race-craft. I would like, at some point, to offer the profession teaching materials on Kant’s racism.

I would also like to offer to philosophers the message that they should get out of their disciplinary silos and read around promiscuously. For my sixth year at Vanderbilt, I had the benefit of doing a fellowship, through the Robert Penn Warren Humanities Center at Vanderbilt, with a bunch of women from other disciplines. It was amazing to cross-pollinate that way. I learned so much about poetry and literature, theology and anthropology, and art and politics from my sister fellows, as I called them, because we were—and, I think, remain to this day—the first all-woman cohort. In the group, I was asked, for example, a very basic question: “Why did you choose to write on the United States?” To which I could only answer that I was trying to comprehend the way that the ideas were lodging themselves in the world, in my world that is, here in the United States.

I wrote about the problems of environmental racism in the case of the skull valley Goshute in Utah, as well as the Diné who have been mining and milling uranium and dealing with the aftermath of that in and around the Grand Canyon in Arizona. In my Kant chapter, I wrote about U.S. prisons as “Human Waste Camps,” as named by Mumia Abu Jamal in his book Live from Death Row. He writes on no-contact visits, strip searches, and solitary confinement, which are three ways in which white America has tried to make waste of Black Americans on a policy and bureaucratic rules-level.

These technologies of violence stem from Kant’s philosophy. Placing a thinker such as Kant among his contemporaries is a good way to see his beliefs in historical relief. For example, Kant’s relationship with Johann Gottfried Herder’s work is especially interesting to read because Herder flatly denied the existence of race and objected to sorting humans into kinds. They argued about race and referenced one another. Doing this work takes some of the power away from the idea that “Oh yeah, everyone was racist back then” arguments. Because, no, Herder was not categorizing people based on Keime, the German word for “seeds” which was Kant’s pseudoscience race philosophy, a philosophy that he believed, espoused, and taught countless people throughout his life.

Kant was invested in this work throughout his career. If we think about an academic’s life, Kant’s day-in/day-out bread-and-butter was teaching the idea of race to German youth. He used to regale them with travel stories, even though he himself never left Königsberg. Then he would say things like “Black people are educable, but only in the capacity that you can train them to be servants.” He thought this allegedly natural characteristic inheres in their flesh. This man was not the genius everybody thinks that he was.

That was part of Kant’s habits of life; he lectured on anthropology throughout his career. It was his most taught class over the span of, I think, about 25 years that he taught that class. He taught geography before that, in which he also characterized people as belonging to kinds, ranking them as well naming who is and who is not educable.

Kant wanted to disseminate these ideas to the next generation of young people and thought deliberately about everything that he did. I mean, Kant was a legit race proselytizer. And a dehumanizer. I am influenced by the work of J. Kameron Carter on Kant and race, a book that I would not have read if I had not met the other fellows from the Robert Penn Warren Humanities Center at Vanderbilt. Carter argues in Race: A Theological Account that “Enlightenment as Kant envisions it is the mutual encoding of the racial and the theological so as to yield the cosmopolitical.” This excerpt from Kant means that the sort of dream of the Enlightenment, its coming to fruition, would be when whiteness and Christianity merge and form a universal power to govern the governments; Kant’s political dreamland is where white European interests govern the globe.

I literally have read everything that Kant has ever written or lectured on; and I have put a lot of thought into the way it all fits together. The concept of character, I think, is a hinge. I need more time. I think of my dissertation as something that I had to write. Not my first book. That will come. My dissertation was the sandbox in which I learned by experimenting and building.

Anyway, discard studies! As I have said, I like cross-pollination and interdisciplinary studies a lot. Discard studies looks at the things that we call “garbage” as material that is laden with meaning about what we value and what we would rather purify than deal with. There are lots of ways of purifying and they are usually violent. I am interested in the ways that we can use impure material, as art, to protest. I am also interested in the way protest and infrastructure and waste triangulate. I see a lot of potential for action and political and ethical meaning-making in this sort of constellation that I am finding here with politics, waste, art, and infrastructure.

I suppose, technically, there was a book by Max Liboiron and Josh Lepawsky called Discard Studies that came out in 2022 after I finished my dissertation. This book is a good introduction to discard studies.

If I could go back and rewrite my dissertation on anything, I think that I would write it on deployments of waste, its intersection with art and with infrastructure in a protest capacity. I am interested in the way art can transform the material–even the bare, least differentiated material–into matter that carries powerful political meanings and speech that can then go on to make material changes in the world. This, it seems to me, is the most powerful alchemy of all.

Dada was, I think, the first movement to use waste in art. Man Ray and Frances Picabia each used waste in their work. I am also interested in the interplay and meaning of the sacred and the profane, which is something fun to trace along with art and waste. I tend to like art–and philosophy too–that is powerful and irreverent, where you sometimes cannot tell if you’re being pranked or not.

Sarah, how would you like to end this interview? Are there topics or concerns that we have not discussed that you would like to address? Would you like to recommend some books, articles, blogs, or videos that readers and listeners can seek out for more information about the issues that you have addressed?

I put together a little sorted bibliography of interesting reading, art, videos, docs, and literature that intersects with some of what I have been talking about in this interview, as well as one must-read on artificial intelligence and two books on policing, tech, and surveillance, since you all live in the world and should know something about these things. Enjoy, friends!

Videos/Documentaries

1. Benjamin, Ruha. 2015. “From Park Bench to Lab Bench – What Kind of Future Are We Designing?” TEDxBaltimore.

2. Muniz, Vik. (artist) 2010. Documentary directed by Lucy Walker. “WASTE LAND.” Accessed September 9, 2024.

3. SFMOMA. “‘Crimes against Photography’: Man Ray and the ‘Rayograph.'” Accessed September 9, 2024.

Art

1. Ofili, Chris. 1996. “The Holy Virgin Mary” The Museum of Modern Art, MoMA. Accessed September 9, 2024.

2. Røstvik, Camilla Mørk. 2021. “Miss Tampon Liberty.” Discard Studies. https://discardstudies.com/2021/06/15/miss-tampon-liberty/

3. Willis Thomas, Hank. 2016. “We the People.” Buffalo AKG Art Museum. Accessed September 9, 2024.

Kant

1. Carter, J. Kameron. 2008. Race: A Theological Account. Oxford University Press.

2. Larrimore, Mark. 1999. “Sublime Waste: Kant on the Destiny of the ‘Races.'” Canadian Journal of Philosophy, Supplementary Volume 25, no. sup1: 99.

3. Mikkelsen, Jon. 2013. Kant and the Concept of Race: Late Eighteenth-Century Writings. SUNY Press.

4. Marwah, Inder S. 2022. “White Progress: Kant, Race and Teleology.” Kantian Review 27, no. 4: 615–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1369415422000334.

5. Huseyinzadegan, Dilek 2018. For What Can the Kantian Feminist Hope? Constructive Complicity in Appropriations of the Canon. Feminist Philosophy Quarterly 4 (1):1-26.

Policing

1. Brayne, Sarah. 2020. Predict and Surveil: Data, Discretion, and the Future of Policing. New York: Oxford University Press.

2. McQuade, Brendan. 2019. Pacifying the Homeland: Intelligence Fusion and Mass Supervision. Oakland, California: University of California Press.

Waste

1. Anderson, Warwick. 1995. “Excremental Colonialism: Public Health and the Poetics of Pollution.” Critical Inquiry. 21 (3).

2. Forbes, Drew. Society and Space. “The O’Hare Shit-In: Airports, Occupied Infrastructures, And Excremental Politics.” Accessed September 9, 2024.

3. Liboiron, Max and Josh Lepawsky. 2022. Discard Studies: Wasting, Systems, and Power. Boston: MIT Press.

4. Reddy, Rajyashree N. 2021. “OF HOLY COWS AND UNHOLY POLITICS: Dalits, Annihilation and More-than-Human Urban Abolition Ecologies.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 45, no. 4: 643–57.

Currently Reading & AI Book:

1. Benjamin, Ruha. 2024. Imagination: A Manifesto. New York: Norton.

2. Crawford, Kate. 2022. Atlas of AI Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sarah, thank you so much for the many resources that you have offered in addition to your enormously thought-provoking remarks throughout this interview. You have given our readers and listeners a great deal to consider and, ideally, act upon.

Readers/listeners are invited to use the Comments section below to respond to Sarah Gorman’s remarks, ask questions, and so on. Comments will be moderated. As always, although signed comments are preferred, anonymous comments may be permitted.

The entire Dialogues on Disability series is archived on BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY here.

From April 2015 to May 2021, I coordinated, edited, and produced the Dialogues on Disability series without any institutional or other financial support. A Patreon account now supports the series, enabling me to continue to create it. You can add your support for these vital interviews with disabled philosophers at the Dialogues on Disability Patreon account page here.

__________________________________

Please join me here again on Wednesday, October 16, 2024, for the 115th installment of the Dialogues on Disability series and, indeed, on every third Wednesday of the months ahead. I have a fabulous line-up of interviews planned. If you would like to nominate someone to be interviewed (self-nominations are welcomed), please feel free to write me at s.tremain@yahoo.ca. I prioritize diversity with respect to disability, class, race, gender, institutional status, nationality, culture, age, and sexuality in my selection of interviewees and my scheduling of interviews.