Hello, I’m Shelley Tremain and I would like to welcome you to the one hundred and twenty-second instalment of Dialogues on Disability, the series of interviews that I am conducting with disabled philosophers and post to BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY on the third Wednesday of each month. The series is designed to provide a public venue for discussion with disabled philosophers about a range of topics, including their philosophical work on disability; the place of philosophy of disability vis-à-vis the discipline and profession; their experiences of institutional discrimination and exclusion, as well as personal and structural gaslighting in philosophy in particular and in academia more generally; resistance to ableism, racism, sexism, and other apparatuses of power; accessibility; and anti-oppressive pedagogy.

The land on which I sit to conduct these interviews is the traditional ancestral territory of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabeg nations. The territory was the subject of the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement between the Iroquois Confederacy and the Ojibwe and allied nations around the Great Lakes. As a settler, I offer these interviews with respect for and in solidarity with Indigenous peoples of so-called Canada and other settler states who, for thousands of years, have held sacred the land, water, air, and sky, as well as their inhabitants, and who, for centuries, have struggled to protect them from the ravages and degradation of colonization and expropriation.

My guest today is Vanessa Wills. Vanessa is Associate Professor of Philosophy at The George Washington University in Washington, DC. She specializes in moral, social, and political philosophy, 19th Century German philosophy (especially Karl Marx), philosophy of race, and philosophy of gender. She is the author of Marx’s Ethical Vision (Oxford University Press, 2024).

[Description of image below: a photo portrait of Vanessa, a Black woman with short hair, who is looking directly into the lens. She is wearing a cowl-neck sweater, a multi-coloured necklace, and dangling earrings.]

Welcome to Dialogues on Disability, Vanessa! Please tell us about your background and educational history, as well as how they led you to pursue a Ph.D. in philosophy.

Shelley, thank you so much for inviting me to share my experiences with you and your Dialogues on Disability readers and listeners. It means a lot.

Well, to start from the beginning, I was raised by my parents in a working-class Black neighbourhood in northwest Philadelphia called “Germantown.” My earliest memories of Germantown were of a community alive with the art, music, food, and cultures of the African diaspora. Both of my parents—still very much alive and kicking—are immigrants from Guyana. I remember walking with my mom to a Caribbean grocery store nearby our home to pick up the items necessary to make daal, chicken curry, fried plantains, saltfish, and other staples of Guyanese cuisine.

In general, Philadelphia is a city that highly prizes mural art. So, I remember a world sparkling with colour and expression. I was always a very curious child; I remember feeling that the Germantown neighbourhood provided a lot of stimulation to reward that. My father was a high school Biology teacher in the School District of Philadelphia—reliable, steady work that engaged his intelligence, creativity, and kindness. Together with the seasonal work he sometimes picked up over the holidays or during summers, and my mother’s skilled and clever homemaking, it was enough to keep the four of us—my parents, my sibling, and me—housed, clothed, and fed.

My earliest memories of experiencing education take place in my family home, where my parents tended to divide pedagogical duties. Both my mother and father would teach us reading and writing; and then, as I got older, my mother tended to be head writing instructor in the family. I learned so much from her about how to write. As kids, my dad would also teach us math and science; my mother would also teach us music and arts-and-crafts. My mother was a “stay-at-home” mom and she lavished my sibling and me with attention. My parents took us to museums and on trips around the city. I was a very fortunate child. I think all these experiences gave me, from a young age, a very positive association with learning.

There is no doubt that the fact that my dad was a teacher influenced my later decision to become a professor, although my parents always wanted me to become a lawyer! For me, it was not so much an explicit, “I am going to be a teacher, just like my dad.” But the example of my father was part of what led me to see teaching as very noble work. He was extraordinarily committed to his students and well-loved by them. He took the work so seriously and it was engrained in his identity. The rhythms of the academic year were also very engrained in my being. Life followed that cadence for me at school as well as at home, even though my father often also picked up summer teaching to make ends meet for the family.

Growing up with curious, creative, and encouraging parents in a diverse and stimulating place like 1980s/90s Philadelphiaꟷwhich I could explore independently due to a robust public transportation infrastructureꟷhas so much to do with how I developed what one could call a “philosophical outlook.” If Aristotle is right and philosophy begins in wonder, then it seems relevant that growing up in that environment meant never growing out of that permanent state of wonder that children have when they are young. My world felt very large, wonderful, and strange with layers everywhere for me to peel back.

In my junior year of high school, I received a letter sent to students that year who had scored in the top percentile of a national standardized test, the PSAT. The letter was from the Telluride Association, inviting me to apply for a fully-funded summer program for rising high-school seniors. I applied and was selected to join a small group of high schoolers from around the country on the campus of St. John’s College, in Annapolis, Maryland, for a six-week program on language and literature. One of the books assigned to us was Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. I had never read a work of academic philosophy before. I was hooked! It is hard to say what it was, exactly, that fascinated me about Wittgenstein. I wrote a lot of poetry as an adolescent, however, and so I think his aphoristic style appealed to me in part for that reason. Moreover, I think his dissatisfaction with mere puzzle-solving really resonated with me, as did the question of how people come to understand one another and share language and ways of encountering the world.

When I got to Princeton University a year later, taking more philosophy classes was high up on my list of priorities. I enrolled in a seminar taught by the philosopher, Jeffrey Stout—the title was, “Dewey, Heidegger, and Wittgenstein.” You know: a gentle introduction to college-level philosophy. My peers were a few college seniors, some grad students, and some seminarians, as Professor Stout taught in the Religion Department at Princeton. Among many things that I learned that semester was that I apparently had a knack for this. Professor Stout was incredibly pedagogically demanding and exacting. He instilled in me an insistence on seeing philosophical inquiry all the way through, to try my best to get things right. He set a very high standard and was certain that I could meet it. The confidence that he had in me both boosted my confidence and meant I had my work cut out for me!

After that initial foray, I took another philosophy class, and another, and soon decided that I would major in philosophy. Among my reasons for doing so was that philosophy could be quite broad and grow with me as my interests changed. I think that has been the case! I often marvel at the decisions which I made as a teenager that actually turned out okay. That was one of them.

With respect to getting a Ph.D. in philosophy, basically, by the end of my junior year in college I was starting to panic because I knew that I had only a year left and that would not be enough time to learn as much as I wanted to learn about philosophy. So, getting a Ph.D. felt completely urgent. I remember pulling extra hours at my work-study job in order to afford the application fees. It really was a major undertaking, especially given my working-class background—the financial cost of even just applying to graduate school can be steep.

Vanessa, you recall experiences of ableism and racism from early in your education. Please describe these experiences and the formative effects they had on your self-understanding and your eventual identity as a philosopher.

I was always very successful in school: a “straight-A” student. Yet my achievements did not protect me from having a bizarre and indelible experience with intellectual ableism (and I would think also racism and sexism) when I was in second grade. The Philadelphia School District had “Mentally Gifted (MG)” classes for students identified as academically advanced. Because I was thriving in my classes, my school suggested to my parents that they should consent to have my I.Q. tested which would determine whether I qualified for the MG class.

One day, a psychologist took me out of class and to a table in the empty cafeteria where he asked me a number of questions and gave me some puzzles to solve. A short time later, he broke the news to my parents that, in his professional opinion, I was “retarded”—which was the terminology that people used back then. I do not know how or why this psychologist came to that conclusion.

To begin with the obvious, however, the students in the “Mentally Gifted” program were disproportionately white, although the student body of the school was overwhelmingly Black. My parents do remember a few of the comments that he made to support it. Apparently, I had asked him whether the I.Q. exercise was a test. He had not told me that the exercise was a test. Instead, he was just a strange man who showed up to take me out of class and instruct me to do puzzles in the cafeteria! I suppose my unwillingness to treat as totally obvious what he thought ought to have been totally obvious was a sign of my diminished “intelligence.” Precisely this alleged trait has been invaluable to me in my life and career.

I think that my encounter with that psychologist is a good example of how Black children get stigmatized and discarded very early, especially when we consider the history of abuses that have been heaped upon neurodivergent children and children with learning disabilities. In the end, I was re-tested and was placed with the “mentally gifted” children. My parents had to really go to bat for me, however—even when it should have been obvious that my actual performance in school obviously trumped a poorly-administered “I.Q.” test. I was fortunate to have confident, highly educated, and involved parents. When I think back about that event, I wonder how many children were pigeonholed the way that man had tried to do to me.

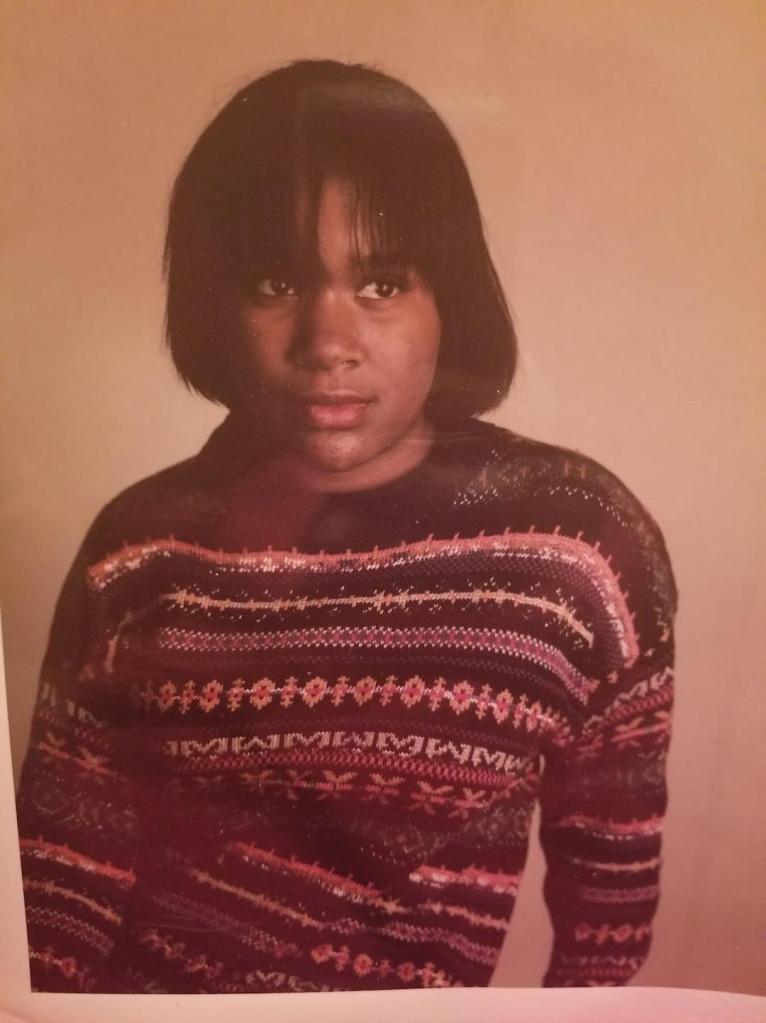

[Description of image below: photo of Vanessa as a teenager. She has a chin-length bob with bangs and is wearing a ski sweater.]

I have experienced ableism and other kinds of discrimination and oppression throughout my life; however, another period in particular that stands out to me occurred during my time in graduate school. I had begun to experience extreme pain, but I did not know it for what it was. I would spend days on end almost confined to my bed by the pain. Then, I developed really painful tendonitis in my feet. I visited doctors but their remedies helped little.

Looking back, I now see that these bouts of pain were likely early symptoms of autoimmune disease. In my first year of graduate school, I began to experience profoundly uncomfortable symptoms associated with menopause, some of which were incredibly disruptive and uncomfortable. I had hot flashes, which is actually kind of a misnomer. They were terrible episodes. First, I would feel disoriented and dizzy. Then, my eyesight would get blurry. Next, I would break out in a flop sweat and become unbearably overheated. Finally—could be thirty seconds, could be many minutes—the heat would subside and then I would be racked by chills. Once the chills subsided, the “hot flash” would be over—for the time being.

I sought medical care and, after insisting on appropriate medical texts, I was told by my doctor that I had something that, back then, they called “premature ovarian failure.” Now it is called, “primary ovarian insufficiency.” In my case, my immune system was attacking my ovaries which caused me to develop symptoms of menopause and to become infertile. I was 22 years old when I got that news. During this time, my mother was also fighting bilateral breast cancer.

It was an incredibly difficult period for me personally and for my family. Any sign of struggle on my part seemed to be taken as evidence that, perhaps, I was not cut out for intellectual life and did not care enough about philosophy. A faculty member whom I had trusted turned out to be quietly using their influence to try and push me out. I felt so disappointed and betrayed by this, but I managed to hold on. Thankfully, the faculty members who ultimately formed my dissertation committee were all fantastic and very supportive. Because I was still afraid of financial retaliation, I resolved not to depend on my graduate stipend to fund my Ph.D. as, were that funding to be suddenly withdrawn, I would be forced out of the program. The next year, thankfully, I won a dissertation fellowship at the University of Rochester and, the following year, I won a Fulbright and studied at Humboldt University.

When I got the Fulbright, I felt that I could finally breathe easy about my detractors. But I had to work at least twice as hard to get half as far, winning external acknowledgement to quell all doubts that I truly belonged in the program. Imagine doing all of this while experiencing chronic disease, for at the time, I had also begun to experience the severe chronic pain that I would later learn was due to psoriatic arthritis, an inflammatory autoimmune condition. That was an incredibly difficult time which has not really ended. I had two hip replacements while bringing Marx’s Ethical Vision into the world.

How have these early educational experiences and your experiences of chronic pain conditioned and shaped your interactions with your students and your pedagogy?

Students are struggling through so much, especially in the long aftermath of the COVID-19 lockdowns and all the continuing effects of the still-unfolding pandemic. And that is in addition to all of the other ways that life can throw curveballs through mental and physical health challenges and other personal obstacles. In addition, we have dire political and economic conditions that are a major stressor for students, especially students heading out into the job market. I know a lot about what it is like to push and push to do your best even when, or especially when, the deck seems stacked against you. So truthfully, I worry much less about showing too much compassion to students than I do about considering that they are human beings, like everyone else, and often will require understanding. I know all too well how obstacles like the ones that I have experienced push people out of the academy. I want my students to know that I see them and understand that they have a whole life that exists outside of my classroom.

I try to find ways to accommodate different personalities and learning styles in the classroom. For example, class participation is a core component of many of my lesson plans. But I offer multiple ways in which students may participate, including through verbal in-class discussion, composing questions and ideas that I can in turn respond to in my own lecture, and/or through discussion-board posts of enhanced length or number. I want to both set high standards and be flexible about expectations, for example by inviting students to rigorously analyze texts, “common-sense” assumptions, and their own ideas, while offering flexibility in terms of how students can demonstrate to me that they are doing that.

Vanessa, you recently published Marx’s Ethical Vision. Many philosophers may find the title of the book surprising. Typically, Marx is not regarded as a moral philosopher first and foremost, an understanding of him that you, however, wish to dispel. Please outline your aims in the book and how you achieved them.

I will begin by saying that I actually agree that Marx is not first and foremost a moral philosopher. I think that many of his interpreters who bristle at reading him as a moral philosopher have some reasonable concerns about moral philosophical readings of Marx. The most significant concern among them is the worry that focusing on the moral aspects of Marx’s work lends itself to readings of Marx that jettison his claims to objectivity and scientificity as somehow hokey, old-fashioned, or embarrassing. The materialist conception of history is, however, Marx’s greatest contribution to human understanding and is totally indispensable to the analysis of class societies. Emphasizing the moral aspects of Marx’s thought can be a way to downplay or deny the importance of the materialist conception of history, as though he was only useful for telling us about what there should be, as though he offered us neither a guide for how to bring that into being or the correct analysis of the conditions in which we find ourselves now.

Marx has commitments to methodological holism, to the centrality of conflict and antagonism in driving historical development, to the importance of analyzing scientifically both what is and what is not. All these commitments can strike some of his interpretersꟷespecially analytic philosophersꟷas the symptoms of a grave Hegelian hangover. From that point of view, the task would be to purge as much as possible of the supposedly mystical and unscientific Hegelianism from Marx. One of the aims of my book is, therefore, to show that dialectical method is central to Marx’s outlook. Indeed, Marx’s project stands or falls with his dialectical method. Dialectical method can be used to understand this age-old question: “Did Marx have a moral theory?” So, that is what I wanted to do: to answer this question using and demonstrating Marx’s method.

That is to say, I do not think Marx is making statements only about the world as it already is or only about what ought to be. I think that Marx’s point is precisely that there is no rigid, abstract opposition between the two. Part of what already is is the world that ought to be. One does not, therefore, abandon science and retreat to some other realm in order to make statements about what ought to be. When Marx looks to the proletariat as “the class with the future in its hands,” it is not because he only wishes it to be so. He thinks that the proletariat really does embody the new world in the old. In describing the character and development of the proletariat as it seeks workers’ emancipation, Marx thinks that he can discover and explain those conditions which have the potential to finally bring about real human freedom, individuality, sociality, and flourishing.

One ought always seek to be representing, philosophically and conceptually, the real, concrete movement and development of the working class. The questions, then, become: How is it that the working class creates the world in which we find ourselves? And how might the working class forge a new world? Questions about what that world ought to be like are not merely abstract. Rather, they are questions about what kind of world is compatible with workers’ full emancipation. That can only be a world in which all human beings are emancipated and live in full accordance with their nature as free, creative, and social individuals.

This “vision” might sound rather “mystical” from an analytic philosophical point of view. I do not pretend otherwise. So, part of my work throughout the book is to explain why you should hear me out. I do that both by demonstrating that Marx himself had lots specifically to say about moral philosophy that we often simply ignore—because it doesn’t fit into our preconceptions of Marx as an “amoral” thinker—and by showing that what he said was often incredibly sophisticated and illuminating. I also develop Marxist interventions into a range of moral debates, in the expectation that readers will see there are ample resources in Marxist thought to advance moral philosophical conversations. One of my hopes is to show that Marx was not some hopelessly muddled thinker, but rather a thinker that we should emulate as we attempt to navigate the existential threats that face humanity today.

Your current book project revolves around Black women Marxists’ views on race, gender, and class. Please describe the book and your motivations for writing it.

So yes, my current book project is about Black woman Marxists’ views on race, gender, and class. I was led to this project in part by my interest in debates among Marxist, Critical Race Theory, and intersectional approaches to the relationship between race, gender, and class. One of the insights of intersectionality is that race, gender, and class each function as vectors of oppression, that it is a mistake to “reduce” any of these categories to one of the others. This insight is at times expressed as a rejection of Marxist approaches to understanding gender and race, approaches that are said to engage in “class reductionism.”

What is “class reductionism”? I understand it as the claim according to which race, gender, and other social categories that are not principally defined by their role in economic production are somehow less real, less determining, less significant, and therefore less worthy of the attention of progressive activists for social justice. A class reductionist approach might advocate that instead of aiming directly at antiracist or antisexist measures, we should instead simply work for socialism and for ameliorations that affect people as workers and not as people who are raced or gendered in specific ways.

Historically, Black woman Marxists—thinkers such as Angela Davis, Claudia Jones, Shirley Graham Du Bois, Louise Thompson, and others—have thought through the relationships among race, gender, and class in ways that put class at the center while avoiding the pitfall of “reducing” either race or gender to economic class. Their work has served both as a corrective to comrades in their own organizations who sought to sideline the importance of Black struggles or of women’s rights and as an example of how Marxist theory is not in fact “class reductionist” (in the manner described above). That is, it has served as an important intervention in debates around race and gender that overlooked the part of women with respects to antiracist struggle, of Blacks with respect to antisexist struggle, and of working class demands with respect to both.

Each of these women became targeted by the carceral U.S. state. Angela Davis was, of course, the central figure in a massive international campaign to secure her freedom after she was framed as an accessory to murder. Assata Shakur was convicted of murder and is a refugee in Cuba. Shirley Graham Du Bois was targeted by the FBI for her activism; her 1068-page FBI file is even 300 pages longer than that of her well-known husband. Black woman Marxists have always been drawn into resistance to the carceral state, both because of where their interests lead them and because of the ways that carcerality has targeted them in order to silence, suppress, and extinguish them.

One of the figures with whom I engage in this new book project is Claudia Jones, a Trinidad-born Black woman who, as a child, emigrated to the United States with her family and who, later, joined the Young Communist League, attracted by their activism in support of the Scottsboro Boys. Claudia Jones died young—she had a fatal heart attack at age 49. She had been disabled throughout her life by a case of tuberculosis in her teens, had been jailed multiple times, and was eventually deported from the U.S. She spent her last years living in London, England. I think a lot about the political stress and trauma that Jones experienced throughout her life and how this stress and trauma may have contributed to her early passing. I also think a lot about what my foremothers have to teach me about striking a balance between doing the important work now while there is time and living to fight another day.

Vanessa, how would you like to end this interview? Are there topics or concerns that we have not discussed that you would like to address? Would you like to recommend some books, articles, blogs, or videos that readers and listeners should explore for more information about the issues that you have addressed?

It may seem like a bit of a cop-out, but I don’t think I have anything more to add! However, I can tell folks about a few things that I have been reading and enjoying lately. Maybe these books give a sense of where my head is at, these days!

Robin Blackburn, An Unfinished Revolution: Karl Marx and Abraham Lincoln

Darryl Bullock, Queer Blues: The Hidden Figures of Early Blues Music

Kate Manne, Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia

Christoph Schuringa, A Social History of Analytical Philosophy

Erin Chapman, Prove It On Me: New Negroes, Sex, and Popular Culture in the 1920s

Mario Mieli, Towards a Gay Communism: Elements of a Homosexual Critique

Andrea Swensson, Deeper Blues: The Life, Songs, and Salvation of Cornbread Harris

Harriet J. Manning, Michael Jackson and the Blackface Mask

Vanessa, thanks so much for these recommendations and for your engaging insights throughout this interview! I am sure that readers and listeners of this interview have learned from them.

Readers/listeners are invited to use the Comments section below to respond to Vanessa Wills’s remarks, ask questions, and so on. Comments will be moderated. As always, although signed comments are preferred, anonymous comments may be permitted.

The entire Dialogues on Disability series is archived on BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY here.

From April 2015 to May 2021, I coordinated, edited, and produced the Dialogues on Disability series without any institutional or other financial support. A Patreon account now supports the series, enabling me to continue to create it. You can add your support for these vital interviews with disabled philosophers at the Dialogues on Disability Patreon account page here.

__________________________________

Please join me here again on Wednesday, June 18, 2025, for the one hundred and twenty-third installment of the Dialogues on Disability series and, indeed, on every third Wednesday of the months ahead. I have a fabulous line-up of interviews planned. If you would like to nominate someone to be interviewed (self-nominations are welcomed), please feel free to write me at s.tremain@yahoo.ca. I prioritize diversity with respect to disability, class, race, gender, institutional status, nationality, culture, age, and sexuality in my selection of interviewees and my scheduling of interviews.