Hello, I’m Shelley Tremain and I would like to welcome you to the 100th installment of Dialogues on Disability, the series of interviews that I am conducting with disabled philosophers and post to BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY on the third Wednesday of each month. The series is designed to provide a public venue for discussion with disabled philosophers about a range of topics, including their philosophical work on disability; the place of philosophy of disability vis-à-vis the discipline and profession; their experiences of institutional discrimination and exclusion, as well as personal and structural gaslighting in philosophy in particular and in academia more generally; resistance to ableism, racism, sexism, and other apparatuses of power; accessibility; and anti-oppressive pedagogy.

The land on which I am located and conduct these interviews is the ancestral territory of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabeg nations. The territory was the subject of the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement between the Iroquois Confederacy and the Ojibwe and allied nations around the Great Lakes. As a settler, I offer these interviews with respect for and in solidarity with Indigenous peoples of so-called Canada and other settler states who, for thousands of years, have held sacred the land, water, air, and sky, as well as their inhabitants, and who, for centuries, have struggled to protect them from the ravages and degradation of colonization and expropriation.

This installment of Dialogues on Disability is a celebratory centennial edition of the series.

When I started the Dialogues on Disability series in April 2015, I did not imagine the extent to which it would become a vehicle for change in philosophy, increasing the public profile of so many disabled philosophers, pulling them out of the margins of academic discourse, and persistently shining a spotlight on how the neoliberal university bars disabled people from its physical, material, and discursive spaces. From April 2015 to May 2021, I produced and edited the series without any institutional support or other funding. Since May 2021, the series has been supported by devoted subscribers to the Dialogues on Disability Patreon.

A few months ago, when I realized that the 100th installment of Dialogues on Disability was imminent, I contemplated various ways to mark the occasion as memorable. I decided to provide a forum for the alumni of interviewees of the series to articulate how the interviews have impacted their thinking about disability; how their personal circumstances vis-à-vis the profession have changed due to the series and its interventions; how (and whether) the series has affected their political, philosophical, and institutional commitments and identifications; and so on.

So, I invited past interviewees to contribute to this centennial installment by composing a paragraph of approximately 100 words in which they would convey what the Dialogues on Disability series has done for them, has meant to them, what they regard as its value, or any other sentiment that they wished to convey about the series. Given the time of year and the fact that some interviews took place several years ago, I am extremely happy about the number of responses to my invitation that I received.

Below you will find the (unedited) insights and reflections about the series from dozens of past Dialogues on Disability interviewees. The entries are listed in alphabetical order by surname rather than by the date on which the interview was posted to BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY or to the earlier (and now defunct) Discrimination and Disadvantage blog, where the series began. A link to the archived interview that I conducted with each of these disabled philosopher interviewees is embedded under their respective names.

Dialogues on Disability Centennial: unedited and defiant.

_________________________________________________________________________________

AMANDINE CATALA [Description of photo below: Amandine, who has long dark hair, poses in front of a blank wall. She is looking directly into the shot with a pleased expression on her face. Sunlight streams into the space from a window to Amandine’s left.]

“With her wonderful and important series Dialogues on Disability, Shelley has created a forum that genuinely promotes epistemic justice by, among other things, centering the perspectives and experiences of disabled scholars and providing more accurate understandings of disability. The series thereby offers an invaluable opportunity to learn about and reflect on ableism in philosophy and academia and to discover the fascinating work of many disabled philosophers. The success of the series is a testament to Shelley’s inimitable leadership and tremendous work to create a supportive and inspiring community for disabled philosophers and for the field of philosophy of disability.”

ROBERT CHAPMAN [Description of photo below: Robert on holiday in Lisbon, Portugal. They are standing in front of an old wooden door with peeling paint and iron bars wearing a backpack, shorts, a brimmed cap, and a t-shirt that bears the image of a walking hotdog and bun wearing a top-hat and holding a cane]

“I first came across the Dialogues on Disability series when I was a philosophically lonely grad student in around 2016. I say “philosophically lonely” since I was one of the few philosophers I knew working on disability, and most of the philosophical work on disability I had found was written by non-disabled philosophers. Dialogues on Disability helped end this loneliness, opening up a rich world of disabled philosophy of disability along with the people behind it. The series has not just showcased community members; it has been part of what has helped us become a community at all.”

MICH CIURRIA [Description of photo below: A headshot of Mich who is looking directly at the camera lens and is smiling widely. Mich’s dark hair and dark v-neck top blend into the background of the shot. ]

“Without Dialogues on Disability (DOD), I wouldn’t be the anticapitalist cripqueer misfit that I am today. Marx said that “philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” This is what DOD does. In contrast to traditional philosophy’s quest for universal principles, ideal theories, and non-anecdotal evidence, DOD allows disabled folks to use phenomenological, narrative, genealogical, and non-ideal analysis to interrogate ableist systems and practices. Simply existing in philosophy as a disabled person is resistance. Using personal stories to challenge the philosophical orthodoxy is another feat. DOD is an oasis of crip solidarity, unruliness, and playfulness in a desert of able-bodied normativity.”

WILL CONWAY [Description of photo below: Photo of Will and two students in a university office. Will, whose hands and forearms are in motion, is sitting on a desk and explaining something to the students in preparation for a collegiate debate tournament. The students, who sit side-by-side at another desk with paper in front of them and pen in hand, take notes as Will speaks. A photo of Foucault and the word POWER are printed on the front of Will’s t-shirt. ]

“If Michel Foucault is correct that his methodology is fundamentally one of bringing subjugated knowledges in discourse to the point of insurrection, then we must admit to ourselves that Shelley Tremain’s work at BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY carries an insurrectionary thread. Far from merely constituting a ‘counter-discourse’ on an institution or industry, Dialogues on Disability always quietly gestures to the distant rumbling of an ongoing war of normalization. It is not a discourse on philosophy, it is a zone of combat in the face of our present ableist and eugenic condition which we must always seek new ways to resist.”

ADAM CURETON [Description of photo below: Adam, the consummate traveller, is standing between two buildings in Salzberg, Austria, and looking into the camera. He is wearing a ski jacket, denim jeans, and a large shoulder bag with a long strap, is holding a take-out coffee cup in his left hand, and his right fist is closed around the strap of the bag. An arched doorway between the buildings can be seen in the background of the shot. Beyond the open iron gate of the doorway, grass, trees, several people, and a walkway can be seen.]

“Dialogues on Disability continues to play an enormous role in creating and sustaining a community of disabled philosophers and others who are committed to advancing philosophical discussions of disability and advocating for structural changes to make the field of philosophy more inclusive for disabled people. Tremain’s incisive questions get the best out of her guests, while her tireless efforts producing this groundbreaking series provide a one-of-a-kind forum for disabled people and others to share their perspectives and make their voices heard. The people she invites, the issues she tackles, and the conversations she has had have put disability and disabled philosophers at the forefront of many ongoing philosophical conversations.”

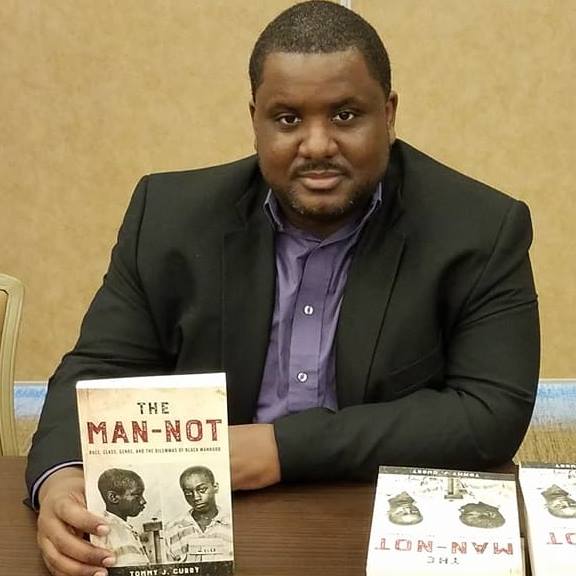

TOMMY CURRY [Description of photo below: Tommy, who is wearing a suit jacket and button-down shirt, sits behind a table at a book launch for The Man-Not. He is looking directly at us. With his right hand, Tommy is holding a copy of the book upright in order to display its cover. The cover of the book comprises two police mugshots of George Stinney Jr., the title and subtitle of the book, and Curry’s name. Additional copies of the book are stacked on the table.]

“Dialogues on Disability is at the forefront of conversations dealing with the marginalization, trauma, and stigma of disability. In sharp contrast to the routine discussion of disability and pain management as additional or compounding disadvantageous identities, Dialogues on Disability pulls the reader into a world fraught with the condition—the living existence—of disability. Over the last several years, conversations on disability have forced a reorganization of how one must think about and think with disabled colleagues. Personally, Dialogues on Disability is one of the only, if not the only, forum to entertain serious discussions concerning race and disability, especially among Black men and boys. This platform is changing public philosophy and how disabled philosophers are made public.”

C DALRYMPLE-FRASER [Description of photo below: C, a white person with facial hair, is sitting in a brightly lit office, facing the camera and faintly smiling. They are wearing round glasses with a golden glasses-chain, a vertically striped, button-down shirt, and a jacket with a floral design. Books on bookshelves fill the background of the shot.]

“Dialogues on Disability was the first dedicated space for disability and/in philosophy that I encountered, and remains an increasingly rich resource today. As an interviewee, the series helped me to unpack my disability investments as areas worthy of their own study, and to make connections to other disabled scholars. As a reader, it continues to teach and to hold me in the incredible work being done. When parts of academic life have felt so difficult as to be impossible, Dialogues on Disability has held many different possibles in view.”

MEGAN DEAN [Description of photo below: A smiling Megan is standing on a rocky surface at the top of a waterfall that flows between tree-covered mountains. At the centre of the shot, the bottom of the waterfall can be seen in the distance. A patch of cloudy sky can also be seen in the shot.]

“The Dialogues on Disability series has taught me so much about ableism in academia and professional philosophy. It has provided me as a person with chronic pain helpful ways to interpret my own experiences and think critically and strategically about my place within the profession. It continually calls my attention to the possibilities for and urgencies of disability activism and solidarity, and reinforces the relevance and importance of teaching about and centering disability wherever and whenever possible. And I so much appreciate being introduced to the many interesting, vibrant, creative, and thoughtful interviewees and their work. Thank you, Shelley!”

EMILY R. DOUGLAS [Description of photo below: Shot outdoors, this photo shows Emily, who is wearing a t-shirt that reads “GAL PAL,” in conversation with a pair of goats. Emily’s right hand is extended to one of the goats who seems to welcome it.]

“Dialogues on Disability was one of the first, and has been the most consistent, exposures I had online to disabled philosophers that allowed me to see new ways of doing philosophy and being inside and outside of academia. Having my own interview conducted and posted, some years later, has been a crucial turning point in generating rich discussions with networks of disabled philosophers. Again and again, I set aside time to read each new interview in detail, providing valuable textures of lived experience that are often absent in the academy. Congratulations on 100!”

JANE DRYDEN [Description of photo below: photo of Jane, a white woman with cat eye glasses and pink hair, who is standing in front of a very full bookcase. On top of some of the books is a small plush toy version of a gut.]

“Dialogues on Disability showcases the richness of disabled philosophers’ theorizing around disability. For any given topic, philosophy tends to focus attention on a small number of theorists – the ‘big names’ who get listened to, read, taught, and cited most often. Given philosophy of disability’s marginalization within the discipline, this problem is even more pronounced. With this series, however, we get to encounter a wide range of philosophers, from many different positions within the academy, and be exposed to a wide range of understandings of disability and its role in the discipline and their research. This can help shape new priorities.”

GEN EICKERS [Description of photo below: Gen, who is listening to music through earbuds, stands in a cornfield in the south of Germany on a sunny day. The sun, whose rays shine through tall cornstalks behind Gen and conceal a portion of their face, sits in a bright blue sky that has patches of cloud.]

“The Dialogues on Disability series has greatly enriched my thinking about both disability and philosophy of disability. Through reading others’ interviews and my own interviews, I learned about the many different understandings of what disability entails and started to critically engage with my own understanding of disability and self-knowledge via new perspectives on disability. The interviews portray philosophers from a wide range of different social groups, backgrounds, and intersections, and so represent the enormous diversity in the discipline of philosophy but, at the same time, challenge persisting practices in academic philosophy. Philosophy as a discipline continues to need the awareness raising and critical discourse BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY provides.”

JOHNATHAN FLOWERS [Description of photo below: Johnathan, who is seated at a table, speaks to someone from behind a microphone. His hands are in motion to aid the explanation that he offers and his facial expression seems both challenging and questioning. A piece of paper attached to the front of the table has Johnathan’s name on it in large letters. There is a bottle of water on the table]

“Dialogues on Disability is the most comprehensive archive of the experiences of disabled philosophers in and outside of the discipline. No other project in the field serves this function as well as Dialogues on Disability. Dialogues on Disability also serves as a source of hope and guidance for newly disabled philosophers, for students whose philosophical acumen is questioned based on their disability, and for philosophers who find themselves isolated in a hostile field. Put simply, Dialogues on Disability’s greatest value lies in its message to all disabled members of the profession, ‘you are not alone’.”

ÉLAINA GAUTHIER-MAMARIL [Description of photo below: A close-up selfie of Élaina, a disabled woman of colour whose tousled short dark hair is adorned with a bright bandana. She is wearing vibrant eye make-up, striking lip colour, and a dark turtle-neck sweater. Her facial expression is both stoic and inquisitive. A book shelf lined with books and journals fills the faded background of the shot.]

“I found Dialogues and Disability when I felt the most alienated from academic philosophy. These interviews form an important archive, not just for the history of ideas, but for people like me, i.e. disaffected disabled philosophers, that are burning with homeless passions. The Dialogues give us a home to return to, a place to share our joys and our frustrations, to meet kindred spirits. Most importantly, it allows us to be, disabled as we are, without apology.”

AUGUST GORMAN [Description of photo below: photo of August, who is standing immediately in front of a wall, looking up into the lens of the camera and smiling widely. He is wearing a t-shirt, jacket, and glasses with large plastic frames, have short tousled hair and a short beard.]

“In a field where relentless work is often required just to stay afloat and perceived rationality is the currency of power, for those of us with invisible disabilities it can be all too tempting to hide or to downplay how profoundly our vantage point as disabled people can shape our theorizing. Dialogues on Disability is what first made visible to me the fact that I’m not alone and that there is solidarity to be found among my disabled colleagues, in addition to giving me the space to find my voice as a disabled philosopher of disability.”

MELINDA HALL [Description of photo below: Melinda, who is outside, smiles widely for the shot. Her long hair is swept over her left shoulder and a hoop earring on her right ear is exposed. Greenery and a brick wall can be seen in the faded background of the shot.]

“I am a fan of and interviewee for Shelley Tremain’s Dialogues on Disability series. These interviews are a seismic social epistemology project; a venue for disabled philosophers to identify with each other; and, they draw sharp attention to power and disability. The series is a crucial step for disability visibility in philosophy and beyond. Shelley interviews widely; she engages established thinkers and graduate students, revising and reversing hierarchy boldly. She offers opportunity for disabled philosophers and those marginalized in the profession. Without her unflagging editorial expertise, interviewing acumen, and labors, such radical inroads and new connections would be impossible.”

ELVIS IMAFIDON [Description of photo below: Elvis is sitting in a desk chair looking into a computer screen. He is wearing wire-rim glasses and has a shaved head.]

“Dialogues on Disability has been a safe space for disabled philosophers to bridge the gap between their professional and personal lives, to showcase how much our positionality, lived experiences, and ontological and normative commitments as disabled philosophers, impact heavily on our research, scholarship and academic commitments. This is what my interview in September 2016 did for me. It gave me an important opportunity to explain why I passionately research African philosophy in relation to my lived experience of albinism in Africa. More important, Dialogues of Disability has created a unique relational community that reminds the guest that they are not alone in their experiencing of the world.”

STEPHANIE JENKINS [Description of photo below: Stephanie, a white woman with long hair, stands in front of a bookcase full of books and ornaments with her hands and forearms behind her back. She is looking directly at the camera and smiling widely.]

“Dialogues on Disability is an online home for disabled philosophers when many of us are alienated within our departments and the broader profession. It is a community where our lived experience and research are taken seriously. It is a space I can go to not feel alone and energize myself in solidarity with my disabled colleagues. Dialogues on Disability is also a rich repository of scholarship; the interviews serve not only as an opportunity for me to learn about my colleagues’ ongoing research, but also as resource I can provide students who are interested in learning about philosophy of disability.”

SOFIA JEPPSSON [Description of photo below: A selfie by Sofia who is on a walk in a snow-covered forest with her dogs. She is wearing a parka, warm scarf, and toque.]

“Dialogues of Disability always provide a welcome break from mainstream philosophical perspectives, and have alerted me to the works of many interesting scholars I might not have known about otherwise. The interview series is concerned with disability in a wide sense, and there are many quite different experiences highlighted by the interview subjects – but the way we keep referring to each others’ interviews also shows such interesting commonalities.”

KRISTINA LEBEDEVA [Description of photo below: A close-up headshot of Kristina, her head resting against the exterior wall of a building, her eyes downcast. From the photoshoot, Fashioned. Photo credit: Hugh Trimble.]

“I am convinced that Dialogues on Disability has accomplished at least two key things. First of all, we see that lived experience and rigorous philosophical thinking are not only intertwined but merge into a singular phenomenon: thought born from out of disability and pain, thought forever on the verge of collapse into the flesh and the hurt, into the wound and the salt. What’s more, the post-pandemic world has irrevocably deepened the invisibilization of the disabled. Those at-risk are now officially erased from the realm of the social. From this perspective, this interview series is a powerful claim to visibility, to existence.”

PAUL LODGE [Description of photo below: Paul is at a standing microphone performing. Paul’s hands are active on an acoustic guitar, with its patterned shoulder strap, and his eyes are closed as he feels the lyrics and melody of the song that he performs.]

“My interview in Dialogues on Disability came shortly after I had published my article ‘What Is It Like To Be Manic?’ The article was intended to convey some of my thoughts about mania, but it was also an autobiographical act of solidarity with others who have experienced manic episodes. I was therefore delighted when Shelley gave me the chance to tell my story more fully as part of her wonderful ongoing effort to promote community among disabled people and by the fact that it was then shared more widely in the profession via dissemination on Daily Nous.”

JULIE MAYBEE [Description of photo below: Julie is looking directly at the camera and smiling widely. She has a shortish tousled haircut, is wearing plastic-framed glasses a turtleneck sweater, and a blazer.]

“Dialogues on Disability has been and continues to be an important voice in the profession of philosophy, bringing disabled philosophers and their work to light and allowing us to get to know one another—even if vicariously. For me, the series has also helped to build a sense of community for an often-missing piece (to borrow a turn of phrase from sociologist and disability studies scholar Irving Zola) of myself.”

MAEVE MCKEOWN [Description of photo below: a headshot of Maeve, who has long, dark, very curly hair and is wearing glasses. Her head is tilted slightly to her right and she is smiling slightly. Light to Maeve’s left is reflected off the left side of her face.]

“Going into neoliberal academia is daunting for anyone, given the competitive, high-stress environment with few jobs, but going in as a disabled person raises so many questions and concerns. Dialogues on Disability is an invaluable resource, showing that it is possible to be a disabled philosopher, that there are struggles but you are not alone. It also educates people about the experiences of philosophers with disabilities, amplifying our voices and giving the rest of the profession an insight into our experiences. Shelley is a pioneer and has changed the profession for the better.”

NATHAN MOORE [Description of photo below: Nathan sits on a couch with a thoughtful look on his face. He is smiling slightly and wears wire-rimmed glasses. A pillow covered in patterned fabric rests on the couch to his right.]

“The Dialogues on Disability series has been a valuable source of both resistance and hope in the face of ableism within the field of philosophy. Through thought-provoking interviews, it has challenged my preconceptions, broadened my perspective, and inspired critical thinking. The series has not only provided crucial insights into the experiences of disabled philosophers but has also fostered a sense of community and solidarity. The endurance of this series lies in its commitment to amplifying marginalized voices and fostering transformative change, making it an indispensable source within, and beyond, philosophy.”

RICHARD MOORE [Description of photo below: Pictured from the rear and left, Richard is face to face with Bimbo, an orangutan with whom he works, looking directly into Bimbo’s eyes and resting his open right hand on the glass between himself and Bimbo. Facing us, Bimbo, who is shy and prefers indirect eye contact, is returning Richard’s gaze with slightly averted eyes, his head resting against the place on the glass where Richard’s palm rests. Photo credit: Charlotte Broecker.]

“Since the interview with Dialogues on Disability, I identify more openly as a disabled philosopher. Having received both a large grant and a tenured position not long after that interview, I’m also aware of the need for tenured faculty to advocate for others. I try to do this proactively, particularly on issues of workload management, because I know how difficult it can be to maintain a sustainable work-life balance while navigating illness, and how humiliating it can feel to ask for patience and understanding when things get too much. While I haven’t taken on an official advocacy position, it’s something I think about for the future.”

VIRGIL MURTHY [Description of photo below: Virgil, a biracial brown person with wavy black hair, who is wearing a black shirt and floral skirt, stands in the corner of a porch enclosed by a metal fence. She is smiling. The shadow of a nearby tree, out of frame, is visible across her face, right arm, and chest.]

“Dialogues on Disability is the fortress of philosophy of disability. It makes us safe. When I found the series, I’d grown almost unsalvageably accustomed to shaking off my unease at ethics thought experiments about people like me. The conviction these interviews instilled in me—that philosophy could be by and for us—motivated me to change course. Being featured on the series afforded me the opportunity to refine my views for a community I hadn’t known existed a year before. Dialogues has revived my faith in activist philosophy.”

KELLY OLIVER [Description of photo below: Kelly, a white woman, sits in a café, staring at something in front of her. She is wearing large plastic glasses, a collared shirt, and suit jacket with a brooch, looking very professorial.]

“My interview with Shelley for Dialogues on Disability was a liberating moment, but also a scary one. I’d never talked about my intense chronic migraine in a public forum. As I did, it made me realize how embarrassed I was talking about my ‘weakness.’ Coming to terms with those feelings of shame, guilt, and humiliation made me aware of the cultural stigma associated with headaches, particularly migraines. People think it’s all in your head! Without the interview, I don’t think I would have seen the magnitude of the impact of that stigma on my life.”

CHRISTINE OVERALL [Description of photo below: Christine, who is wearing sunglasses, is sitting in a lawn chair on a swimming-pool deck. Two of her grandsons sit in her lap. The three of them are smiling and wrapped in a big beach towel because they have just come out of the pool. Behind them is a fence and a children’s playground.]

“The effects of Dialogues on Disability for me are personal as much as intellectual. I have come to realize that I’m not alone: the disablement of many different types of persons is ubiquitous. In addition, during my 2016 dialogue with Shelley, I realized for the first time just how much I had learned from my Uncle Jack, born in 1928, who was labelled ‘retarded,’ and from two other family members in similar situations. I credit Shelley’s series, and more generally her theorizing about disablement, for helping me to understand all of this. Thank you, Shelley.”

ANDREA PITTS [Description of photo below: Andrea, a nonbinary/trans masculine Latinx person with a short fade haircut, is wearing a collared shirt and leather jacket. They are smiling widely for the camera and standing in front of a wooden structure whose planks are covered in paint that is chipping.]

“Regardless of whether you’re just beginning to learn about philosophy of disability or someone who has been researching disability studies or philosophy for many years, Dialogues on Disability is a fantastic place to engage the most current and cutting-edge conversations in the field. Shelley Tremain’s in-depth interviews offer theoretically rich and existentially nuanced accounts from a wide variety of disabled philosophers across the globe. This blog and Tremain’s work has been filling a gap in the profession of philosophy for years and I hope to see its influence continue to grow in the years ahead.”

KRISTIN RODIER [Description of photo below: A smiling Kristin, who is a fat white woman, is lying on her side, in the grass, with a large dog in front of her. She is wearing a hat and sunglasses. Trees fill the background of the shot and grass with dandelions appears in the foreground.]

“Dialogues on Disability highlights simultaneously a great number of disabled philosophers and the significant exclusion we experience in philosophy. On the strengths of these scholarly engagements and profiles, the sub-field of philosophy of disability can no longer be dismissed as “not philosophy.” Because I made a conscious effort to expose discrimination that I endured for not meeting exactingly narrow standards of who philosophers are and how they should think, my experience was both challenging and opened up possibilities for new connections and support. Dialogues exemplifies a critical and principled stance of refusing to treat exclusions in philosophy as separate from the profession itself, piercing the illusion that it is governed by a meritocracy of ideas and intellects. Congratulations to Shelley and thank you for your hard work and persistence—here’s to 100 more!”

ERIC SCHLIESSER: [Description of photo below: headshot of Eric who is smiling slightly and has black plastic sunglasses propped up on his head. He is wearing a dark t-shirt.]

“Dialogues on Disability has introduced me to a community of thinking about living with unexpected hard and simultaneously evolving constraints. I am grateful to Shelley for her activism, and care.”

NANCY STANLICK [Description of photo below: Nancy, who is in an office, is looking down, perhaps at the computer taking the photo, and is smiling. Nancy is wearing wire-framed glasses, a white shirt, and dark jacket, and has short brown hair.]

“The series has helped me recognize multi-faceted ways in which disability affects the work and lives of disabled philosophers. It has sharpened my focus on ways in which disability affects our professional activity, and how our situatedness enhances our teaching, research, and pedagogy. I’ve noted that series readership is impressive in number and a few people have contacted me regarding their own disabilities. I think a primary benefit of the series is public, straightforward, and honest statements of disabled philosophers regarding the value and contributions they make despite and because of disability.”

__________________________________________________________

There it is. One hundred installments of Dialogues on Disability, the series of interviews that forges a safe environment and welcoming philosophical and political community for disabled philosophers. Many thanks to all the courageous and compelling disabled philosophers who have shaped the series and have rendered it the premier arena of resistance against the ableism and exclusion that disabled philosophers confront in philosophy and beyond.

I will continue to host and produce Dialogues on Disability until, well, I decide to stop doing it. Thank you for your unwavering loyalty to the series. You can also show your appreciation and support for the series by becoming a contributing member of the Dialogues on Disability Patreon here.

Take some time today to explore the entire Dialogues on Disability archive of interviews here.

And please join me here again on Wednesday, August 16th, 2023, for the 101st installment of the Dialogues on Disability series and, indeed, on every third Wednesday of the months ahead. I have a fabulous line-up of interviews planned. If you would like to nominate someone to be interviewed (self-nominations are welcomed), please feel free to write me at s.tremain@yahoo.ca. I prioritize diversity with respect to disability, class, race, gender, institutional status, nationality, culture, age, and sexuality in my selection of interviewees and my scheduling of interviews.

[…] Dialogues on Disability: Centennial Edition […]

LikeLike